School of Athens

- Date of Creation:

- 1510

- Height (cm):

- 500.00

- Length (cm):

- 770.00

- Medium:

- Other

- Support:

- Other

- Subject:

- Figure

- Technique:

- Fresco

- Framed:

- No

- Art Movement:

- Renaissance

- Created by:

- Current Location:

- Vatican City, Holy See (Vatican City State)

- Displayed at:

- Vatican Museums

- School of Athens Page's Content

- Story / Theme

- Inspirations for the Work

- Analysis

- Critical Reception

- Related Paintings

- Artist

- Art Period

- Bibliography

School of Athens Story / Theme

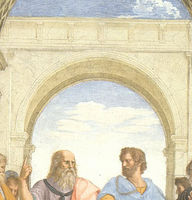

Raphael's School of Athens was not meant as any type of school that actually existed (i. e. Plato's Academy) but an ideal community of intellects from the entire classical world. To facilitate this vision, Raphael created a spacious hall that recalls the "temples raised by philosophy" written by the Roman poet Lucretius.

The School of Athens demonstrates, like classical statues or clear and distinct ideas, idealized portraits of Raphael's contemporaries representing the major figures of classical wisdom and science. Taken further, Raphael painted on the Vatican Palace's walls his vision of the world of Humanist thought.

In the center of the artwork, Plato and Aristotle are discussing the respective merits of Idealism vs. Realism. Plato holds his book, Timaeus, one of the few works by Plato that had been recovered by the Renaissance, while explaining how the universe was created by the demiurge from perfect mathematical models, forms and the regular geometric solids. With his right hand Plato gestures upwards, indicating that the eternal forms, such as the ideals of Beauty, Goodness and Truth, are not in or of this world, but beyond, in a timeless realm of pure Ideas.

In argument Aristotle points with his right hand straight ahead out into the solid world of material reality, into the world of physical science and practical reason. In his left hand Aristotle holds his Ethics.

It was part of the Renaissance's mystique that immortality in this world could be achieved through reincarnation of some immortal deity or hero from the past. Therefore it can be seen as Raphael's great tribute that he included Michelangelo and his contemporaries in the artwork in the shape of great philosophers and scientists.

On either side of Plato or Aristotle are the main thinkers of the classical world. The philosophers, poets and abstract thinkers are allied on Plato's side. The physical scientists and more empirical thinkers are on the side of Aristotle. Only a few of the ancient thinkers in School of Athens can be identified definitely.

One of whom is one of Plato's masters, the Greek mathematician Pythagoras. Here he is demonstrating, his theory that ultimate reality consists of numbers and harmonic ratios.

The scholar in the white turban and green robe who leans over Pythagoras is the Arabic philosopher Averroes. Averroes is responsible for transmitting the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle to the West.

In the right foreground are concentrated two groups. An absorbed group of students huddles around the leaning figure of Euclid (who may be Archimedes), demonstrating some geometric proposition with a pair of compasses upon a slate. Behind him, in yellow robes, stands the Greek astronomer and geographer Ptolemy, holding his globe of the earth. Behind him is the Persian astronomer and philosopher Zoroaster, holding a sphere of the fixed stars. Just to the right of these two is Raphael himself, the only figure in the School of Athens who gazes directly back at the viewer.

Sprawled in solitude on the steps before Aristotle is the Cynic philosopher Diogenes, and the brooding figure on Plato's side is supposed to be Heraclitus ("no man can step into the same stream twice"), the pre-Socratic philosopher whose enigmatic observations fit into no clear category.

Other contemporaries of Raphael seem to have been singled out for glorification. Standing next to Raphael on the extreme right is his friend the painter Sodoma. In fact, it was Sodoma's own frescoes that Pope Julius ordered Raphael to destroy for his own. The model for Zoroaster is said to be the humanist scholar Pietro Bembo, possibly a source of many of Raphael's ideas.

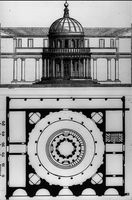

The architect Bramante is portrayed as Euclid (or Archimedes). Bramante was a mentor of sorts and it was probably from him that Raphael got most of the geometry and architectural composition for his painting, as well as many of the philosophical ideas in it.

Leonardo da Vinci's portrait is also self evident in the School of Athens. His reincarnation as Plato is somewhat curious though, given that Leonardo left Florence, and its overt Platonism, for the more congenial Aristotelian circle of scholars, scientists and engineers at Milan. Perhaps it was Raphael's duel admiration and preference for Plato, combined with his respect for his teacher (Leonardo) that led him to identify the two men.

School of Athens Inspirations for the Work

Heraclitus:

There is a great deal of conjecture concerning the solitary Heraclitus figure. Heraclitus was the only figure in the whole School of Athens who was absent from Raphael's preliminary drawing of the painting. Furthermore, technical examination of the fresco confirms that Heraclitus was painted in later, on an area of fresh plaster put on after the adjacent figures were completed. At the time of painting the School of Athens, Michelangelo was working on the Sistine Chapel and despite his efforts to shroud his work in total secrecy, we know Raphael was able to sneak in and have a look. Was this the inspiration for Heraclitus, who not only looks like Michelangelo, with its sculptural solidity, but looks like it was painted by Michelangelo?

After being summoned to Rome by Pope Julius II in 1508, Raphael was charged with painting a cycle of frescoes in a suite of medium-sized rooms in the Vatican papal apartments in which Julius II lived and worked. These rooms, which include the School of Athens, were known as the Stanze.

Raphael's concept for the School of Athens was to bring into harmony the spirits of antiquity and Christianity and reflect the contents of the pope's library with themes of theology, philosophy, jurisprudence and the poetic arts. Raphael's inspiration for the room is worldly and spiritual wisdom displaying the accord which Renaissance humanists perceived between Christian and Greek philosophy. The theme of wisdom is an appropriate inspiration as this room was the council chamber for the Apostolic Signatura where most of the important papal documents were signed and sealed.

Unlike some of his latter frescoes, The Stanza della Segnatura (1508-11) was decorated almost entirely by Raphael himself.

School of Athens Analysis

Perspective:

As a spectator viewing the School of Athens you are made to feel that you could step into the space in this picture, as if walking into a theatrical setting on a stage. There is a series of horizontal planes across the checkered floor, up the steps, past the pillars supporting the barrel vaulting, and into a domed area, which is indicated above the heads of Plato and Aristotle by the curved line under the window.

The all important vanishing point of the fresco is somewhere in the space between the heads of Plato and Aristotle. The use of the sky and the incompleteness of the architecture are indications that the School of Athens is not a physical building that actually existed in the past, nor one inhabited by ordinary human beings. That the vanishing point is constructed in such a carefully considered place (i. e. the heavens) is also a clear gesture that the scene is taking place on some higher plane.

The heads of the Gods Apollo and Athena are aligned with Plato's and Aristotle's heads respectively. The point where the two diagonals intersect can be referred to as the divine center between the two philosophers.

From the right hand side particularly, the School of Athens invites the viewer to see another strong pair of diagonals starting from the extreme lower corners of the picture. Along these diagonals the heads of the Gods line up with their opposite philosophical heads (i. e. Apollo with Aristotle and vice versa). Therefore the dialectical interplay of ideas and reconciliation between the two philosophies goes on.

Color palette:

Though the school of Athens is not necessarily defined by its use of color, its philosophical content displays a wide variety of colors.

Use of light:

The separation between the concrete and the abstract in the School of Athens is developed by its lighting and figures. The lighting is very logical and consistent with reality. It comes from the direction of the window and fills the actual room. However, the philosophers themselves are posed and seen separately, like life models gesturing in the studio. Notice how they don't communicate with one another.

Mood, Tone and Emotion:

His cartoon of the School of Athens show the importance of maintaining the relationship between the figures but also the chiaroscuro effects that are so important for High Renaissance art.

Brush stroke:

Raphael was a perfectly balanced painter and in the School of Athens he demonstrates flawless brush stroke. He used different drawings to refine his poses and compositions, to a greater extent than most other painters judging by the number of variants that survive to this day.

School of Athens Critical Reception

Julius II:

Julius II was a highly cultured man who surrounded himself with the most illustrious personalities of the Renaissance. He entrusted Bramante with the construction of a new basilica of St. Peter to replace the original 4th-century church; he called upon Michelangelo to execute his tomb and forced him against his will to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel; and, sensing the genius of Raphael, he committed into his hands the interpretation of the philosophical scheme of the frescoes in the Stanza della Segnatura.

-

San Pietro in Montorio, Bramante

Raphael's School of Athens achieved immediate critical and popular success. According to Vasari, its beauty and thematic unity were universally accepted. Unlike other monumental works of the era (the Sistine Chapel, for example) its reception was not marred by any reservations concerning its content. The artwork in some respects is comparable to the renown Raphael was held in generally. This is a credible observation given Julius II's original recruitment of Raphael to the Papal court and his subsequent expanded artistic responsibilities following the completion of the Stanze frescoes.

During life:

By the time Raphael's frescoes were complete in 1514, he was one of the most celebrated painters in Europe, largely in part due to the success of artworks such as the School of Athens. As a result of the remarkable success of his Stanza Raphael's artistic responsibilities were greatly extended, eventually becoming responsible for all of the Vatican's art in Rome and becoming of St. Peter's in succession to Bramante.

After death:

Raphael's work has always been highly regarded by his contemporaries and followers alike. However, the School of Athens proved less influential in his own century than works by Michelangelo or da Vinci. It is also accepted that with Raphael's death and the end of magnificent frescoes such as the School of Athens, the classic art of the High Renaissance subsided and was taken in a new direction by Mannerism and Baroque art.

Raphael's School of Athens has always been admired and studied, particularly between the late 17th and late 19th century, where his decorum and balance were lauded. His work was universally seen as the best model for history painting.

By the 20th century and into the 21st the School of Athens is still seen as one of the culminations of art of the High Renaissance.

School of Athens Related Paintings

School of Athens Artist

Raphael is regarded as one of the greatest artists of all time. He was an Italian painter, draughtsman and architect, and is, along with Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Titian, rightfully acknowledged as one of the masters of the High Renaissance.

Some highlights of Raphael's distinguished career include famous altarpieces, a series of Madonna's and frescoes in Rome. In addition to being the most famous painter of the papal court, he ran a large workshop, allowing him to diversify and work as an architect and print designer.

Raphael was a master at using depth and perspective, along light and shadow - the cornerstones of modern day art. Throughout his short life he made some of the most awe-inspiring, beautiful and influential works of art during the Italian Renaissance.

At the time of painting his School of Athens Raphael was at the top of his game creatively. He would have been hugely keen to impress with this being his first major commissioned work since being summoned to Rome. As such his feelings upon painting the School of Athens would have been a mixture of nervousness and exhilaration at being given such an opportunity. Whilst not necessarily aware or knowledgeable regarding the different philosophies he depicted on his fresco, he no doubt would have been influenced by the humanist ideas of Bramante.

School of Athens Art Period

Raphael painted during the twilight years of the High Renaissance, a period of art during the Italian Renaissance between 1450 and 1527. During this time Pope Julius II patronized many artists (including Raphael and Michelangelo) and through his patronage the movement shifted into Rome, having previously been centered in Florence.

Raphael's move to Rome is symbolic of the Art Period's movement itself. Paintings by Raphael and Michelangelo are largely held to be the embodiment of the High Renaissance's style. The style was introduced to architecture by Donato Bramante, who built the Tempietto in 1502.

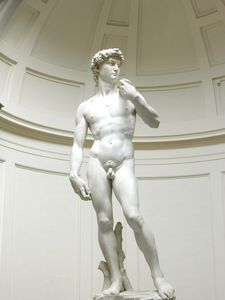

High Renaissance sculpture, as exemplified by Michelangelo's Pieta and David, is characterized by the ideal balance between statics and movement. The High Renaissance is widely viewed as the greatest explosion of creative genius in history. Raphael's death in 1520 and the sack of Rome in 1527 signaled the decline of the High Renaissance.

Raphael's School of Athens like many of his works is not seen as an innovation to the High Renaissance, but more a culmination, displaying his unique talent for absorbing the works and styles of the classics and his contemporaries alike. However, in paying homage to the great thinkers of antiquity there is perhaps no better example of High Renaissance genius, displaying respect to the Classics while exuding all the trappings of Humanist influence.

School of Athens Bibliography

There are countless books written about Raphael and the High Renaissance. Below is a selection of recommended reading on the artist and his works.

• Brown, Clare & Evans, Mark. Raphael: Cartoons and Tapestries for the Sistine Chapel. V & A Publishing 2010

• Chapman, Hugo, et al. Raphael: From Urbino to Rome. National Gallery Company Ltd, 2008

• De Vecchi, Pier Luigi. Raphael. Abbeville Press Inc. , 2003

• Jones, R. Raphael. Yale University Press, 1987

• Talvacchia, Bette. Raphael. Phaidon Press Ltd, 2007

• Whistler, Catherine. Michelangelo and Raphael Drawings. Ashmolean Museum, 1990