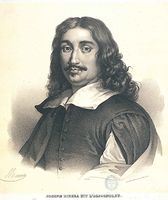

Jusepe de Ribera

- Short Name:

- Ribera

- Alternative Names:

- Josep de Ribera, José de Ribera, Giuseppe Ribera

- Date of Birth:

- 12 Jan 1591

- Date of Death:

- 02 Sep 1652

- Focus:

- Paintings, Drawings

- Mediums:

- Oil, Prints, Other

- Subjects:

- Figure, Fantasy, Scenery

- Art Movement:

- Baroque

- Hometown:

- Xátiva, Spain

- Jusepe de Ribera Page's Content

- Introduction

- Artistic Context

- Biography

- Style and Technique

- Who or What Influenced

- Works

- Followers

- Critical Reception

- Bibliography

Introduction

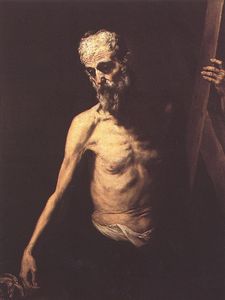

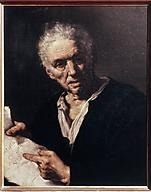

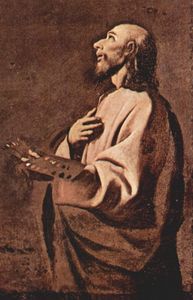

Faces contorted in pain, mutilated bodies, sagging flesh, bearded women and deformed boys: such is the stuff of Jusepe de Ribera's paintings. The fact that Ribera was probably the most influential painter of the Spanish Baroque (even more influential than his far more famous compatriot, Velázquez) tends to be overshadowed by the fact that his often twisted, bizarre images have categorized the artist as a painter of the dark and bloody, and nothing more.

Without a doubt, Ribera was certainly intrigued by obscure and sinister subjects, and these paintings constitute some of his most powerful and influential images. However, what many art enthusiasts do not know is that Ribera is much, much more than a mere painter of oddities.

In fact, a closer look at his oeuvre reveals that the artist was as much a master of Baroque color, dynamism and grandeur as he was a master of Caraveggesque chiaroscuro and naturalism. Furthermore, Ribera's prints and paintings alike had an enormous impact on the development of Baroque art all over Europe.

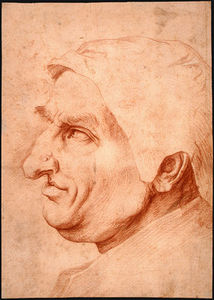

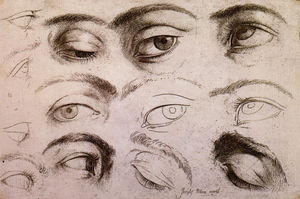

Ribera was a prodigious draftsman and printmaker, with over one hundred surviving drawings attributed to him today. Printmaking (etching and engraving) was a marginal art form in Spain and few major Spanish artists mastered it; in Italy, on the other hand, printmaking was better developed as an art, and Ribera became skilled at etching and engraving techniques after arriving in Italy as a teenager.

Ribera's prints and drawings range from polished academic studies to hasty preparatory sketches for paintings, and constitute a fascinating facet of his oeuvre.

The artist is most famous for his paintings of tortured saints, aging bodies, gruesome martyrdoms and social freaks and outcasts. His oeuvre is not limited to this unusual set of themes, however: Ribera's paintings include biblical scenes, pictures of the Virgin and Child and the Immaculate Conception, a series based on the five senses, mythological subjects, and portraits of real and imaginary figures, both from the past and present.

Ribera's paintings are not only far more varied in scope than many people imagine, but they are also of enormous importance for the future of European art.

Jusepe de Ribera Artistic Context

Technically, Ribera is a painter of the Spanish Baroque: he was born in the Valencia region of Spain and his work essentially determined the direction of art in that nation for the entire 17th century.

Paradoxically, however, Ribera actually lived and worked in the Italian state of Naples for most of his life, stating that Spain was "a loving mother to foreigners and a very cruel stepmother to her own sons. "

Living in Italy, Ribera had exposure to classical and Renaissance art, making his artistic education far broader than any other Spanish artist, and subsequently his art also had a major influence on the development of Italian Baroque art.

Ribera can nonetheless be qualified as a Spanish artist, however, because during the 17th century Naples was actually a Spanish territory; in fact, his major patrons were not Italians, but the governing Spanish class as well as Flemish merchants within the city.

Jusepe de Ribera Biography

Early years:

Jusepe de Ribera was born in Valencia, Spain in February of 1591, the second son of a successful shoemaker. Very little is known about Ribera's life pre-Italy: virtually no contemporary documents exist which could shed some light onto this obscure period.

It is generally assumed that Ribera was apprenticed to successful local artist Francisco Ribalta as a boy, though no evidence actually exists to prove this claim.

Ribera most likely stayed in Spain until he was at least a young teenager; legend has it that he left Ribalta's studio and, subsequently, Spain as the result of an illicit affair with the older painter's daughter.

Ribera is first documented in Italy in 1611, first stopping in Parma, and then arriving in Rome by 1613. While in Rome, Ribera evidently took advantage of the opportunity to study the ubiquitous masterpieces of antiquity, and is documented as having been a member of the Academy of St. Luke until 1616.

Legends abound from this period of Ribera's life, most notably the story that as a poor young art student, Ribera rejected the offer of a wealthy cardinal to support him in a life of luxury, claiming he needed the stimulus of necessity in order to produce his art.

Because he remained fiercely proud of his Hispanic roots, often signing his paintings "Jusepe the Spaniard," in Italy he acquired the nickname lo Spagnoletto, or "the little Spaniard. "

Ribera wound up in Naples by 1616, allegedly in an attempt to track down the artist whose paintings had the biggest impact on him while in Rome - Caravaggio (who by then was six years dead).

Ribera was lucky enough to immediately marry Catalina Azzolina India, the daughter of the successful Neapolitan artist and art dealer (the rapidity of the marriage would suggest that Ribera had already arranged the marriage before even arriving in Naples).

The marriage proved to be quite advantageous; within a few short years, Ribera was hands-down the most popular artist in Naples, receiving the most lucrative and prestigious commissions in the city.

Middle Years:

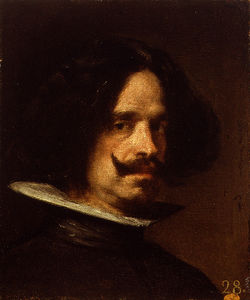

The 1630s and 1640s were wonderfully successful for Ribera: he was awarded with the Papal Order of the Vatican (the equivalent to a Knighthood), Spain's star painter Velázquez came to Naples with the sole purpose of acquiring Ribera's paintings for the pleasure of the monarch, and Ribera was earning enough money to move his family into a palatial estate and establish a thriving painter's workshop.

Inevitably, of course, Ribera's fortunes took a tragic turn for the worse in the 1640s, when the artist fell seriously ill and was unable to work for a significant period of time. Even worse, a populist uprising against Spanish rule in 1647 forced Ribera and his family to take refuge in the Spanish viceroy's palace, and while the Ribera family escaped unharmed, Spain's brutal repression of the uprising damaged the artist's relations with many prominent Neapolitans, resulting in fewer commissions.

Advanced years:

Continuing down this slippery slope, Ribera had a relapse of his illness in 1649 and his already shaky financial situation was made even worse when his eldest daughter had to move back home after the death of her husband only a few years after their wedding.

Ribera even petitioned the King to ask for financial assistance due to money lost during the uprising as well as in compensation for the loss of his son-in-law. But the artist was to die in 1652 in near-poverty before he received the King's reply.

Jusepe de Ribera Style and Technique

Ribera is famous for his Caravaggist, tenebristic style, and for a long time after his death was known as the most important of the 17th century "shadow" painters. Indeed, particularly in his early, pre-1632 style, Ribera was heavily influenced by Caravaggio: his style was notable for its intense chiaroscuro, emphasis on marked, linear contours, lifelike naturalism and dramatic, sometimes downright sinister tone.

After 1632, however, Ribera increasingly painted in an altogether different style, characterized by a much brighter illumination, bolder palette and looser brushstroke; throughout his career, however, Ribera would continue to switch between the two styles, depending on which best suited his subject matter. Ribera is particularly noted for his almost obsessively repetitive depictions of old, deformed, contorted flesh.

Ribera was unusual for a Spanish artist in that he was an excellent draughtsman. This is another example of the Italian influence: there was a strong, long-standing tradition of drawing and printmaking in Italy (as well as elsewhere in Europe) that was lacking in Spain.

Unlike artists like Velázquez and Zurbarán, Ribera was a prolific sketcher and was particularly well-known for his mastery of etching and engraving techniques. In fact, Ribera held the art of drawing in such esteem that in the 1620s, he attempted to compile a teaching manual (which was ultimately unpublished).

Ribera not only sketched in preparation for his final, painted compositions, but also etched his own paintings as a means of recording and distributing (in lieu of photography).

Who or What Influenced Jusepe de Ribera

Ribera was lucky: unlike his contemporary Spanish Baroque artists like Zurbarán, Velázquez and Murillo, Ribera had constant and long-term access to the masterpieces of antiquity, as well as the best of Renaissance and Mannerist art (stuck in Spain, Ribera's compatriots had to suffice with the foreign art works in the extensive royal collections).

Ribera's influences are thus broader and more diverse than those of the above-mentioned artists, and his paintings evidence a much stronger Italianate influence. The following artists were particularly inspirational for Ribera;

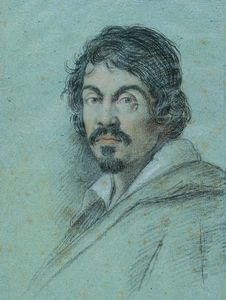

Caravaggio:

This renegade of the Italian Baroque was the major influence on the young Ribera. Caravaggio would already have passed away by the time Ribera made his way to Italy in the early teens, but Caravaggio's paintings would still have been very much alive, and easy for Ribera to see in both Rome and Naples, where Caravaggio lived for some time.

These works had such an enormous impression on Ribera, some contemporary sources say that he was inspired to move to Naples from Rome with the express intent of finding the older artist. In fact, some even say that Ribera studied under the Italian's wing, but such reports are surely fanciful.

The following aspects of Caravaggio's style were of fundamental importance for the development of Ribera's paintings;

Intense chiaroscuro

Rigorous naturalism

Well-defined, linear contours

Raphael:

Ribera's paintings may not demonstrate this influence quite as clearly, but the Spanish artist was devoted to Raphael's work, as well as the paintings of the other titans of the Italian Renaissance (including Michelangelo, Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese).

Ribera was particularly influenced by the artist's classical, formal compositional balance, a balance which always underlines Ribera's works. This Renaissance/classical influence was a big difference between Ribera and other Spanish artists: note, for instance, how space tends to be far better developed in Ribera's paintings than in paintings by Velázquez or Zurbarán.

Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck:

Ribera got to know the work of both Rubens and van Dyck (the brightest stars of the Flemish Baroque) through the collections of Flemish merchants living and working in Naples, who were also Ribera's frequent patrons.

Exposure to the paintings of these two artists (as well as to the artworks of the Venetians) was the major inspiration for the development of Ribera's mature style.

Jusepe de Ribera Works

Jusepe de Ribera Followers

Ribera was perhaps the most influential of any of the great masters of the Spanish Baroque. Because he lived and worked in Italy for his entire career, Ribera's European exposure was far greater than that of his compatriots, who were relatively isolated back in Spain.

Ribera thus had a profound influence not only on the development of Spanish Baroque art, but also on the development of the Italian Baroque and art across the rest of Europe.

Spanish Followers:

Ribera may have lived in self-imposed exile in Italy, but his art was well-known back in Spain. In fact, Velázquez travelled to Naples on one of his trips to Italy on behalf of Philip IV with the express intent of acquiring some Ribera paintings to take with him back to Spain.

Ribera's works could also have been known in Spain through various private collections, prints and copies. Ribera was responsible for exporting Caravaggio's style to Spain: from Ribera, artists like Zurbarán, Velázquez and, to an extent, Murillo learned to use chiaroscuro to define forms and create drama, as well as a sober, unflinching naturalism.

From Ribera, these Spanish artists learned;

To depict religious and/or mythological scenes in a down-to-earth, realistic manner

To use stark chiaroscuro and a limited, sober palette

To create a tense, dramatic atmosphere

Italian Followers:

Unlike other Spanish artists of the 17th century, Ribera had a big and immediate impact on Italian art. Ribera's immediate followers included Luca Giordano and, perhaps most importantly, Salvator Rosa. Rosa, who is often described as an impetuous, rebellious proto-Romantic, was a talented painter and engraver who was particularly inspired by the more dramatic, violent aspects of Ribera's art.

From Ribera, these Italian artists learned:

To use subtle chiaroscuro to create volume and define forms

The realistic depiction of imaginary, ethereal subjects

Sketching and engraving techniques

19th Century Followers:

In the 19th century, Ribera was particularly cherished by the Romantics (painters and poets alike, including Théophile Gautier and Lord Byron), who adored the Spaniard far more for his bloody, bizarre images than for his mastery of chiaroscuro and technical precision.

Compatriot Goya was particularly inspired by Ribera's paintings, as were French artists like Courbet and Manet. While the French artists were particularly inspired by Ribera's realism and subtle use of light and shadow, Goya was above all inspired by Ribera's eerie ability to create scenes of an intensely haunting, bone-chilling terror.

Jusepe de Ribera Critical Reception

As there are so few contemporary documents that could shed some light on Ribera's relatively obscure life and career, Ribera studies were long shrouded in legends, myths, and misattributions.

In the early 20th century, however, art historians finally began to take steps to unravel the threads of Ribera's biography and to properly sort out and catalogue his paintings and sketches. Major strides were made in the 1970s, when a spate of exhibitions highlighting the artist's oeuvre inspired the publication of several important studies and monographs.

Ribera may have been recognized as one of the most accomplished artists of the Baroque, but an utter dearth of contemporary documents or reliable sources concerning the artist's life and career meant that most of what was known about Ribera until the beginning of the 20th century was merely the stuff of legends.

The first attempt to make sense of Ribera's biography and organize Ribera's paintings was the German art historian August Mayer, who made Ribera the subject of his PhD dissertation in 1908. In the following decades, three more monographs on the artist appeared, authored again by Mayer, as well as Elías Tormo and George Pillement, Mayer's being the most important.

In 1925, Elizabeth du Grié published her landmark biography and survey of paintings, which remained standard until the 1970s. In this decade, a spate of exhibitions devoted to Ribera (most notably the Princeton exhibition of Ribera's prints and drawings organized by Jonathan Brown) spurred the publication of several studies on the artist, most notably two catalogue raisonnés (or a book of an artist's complete works): one published by Craig Felton in 1971, and one published by Nicola Spinosa in 1978.

Jusepe de Ribera Bibliography

To read more about Ribera and his paintings please refer to the recommended reading list below.

• Brown, Jonathan. Jusepe de Ribera: Prints and Drawings. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973

• Darby, Delphine Fitz. "Ribera and the Blind Men. " The Art Bulletin 39.3 (Sept. 1957): 195-217.

• Felton, Craig, and William Jordan, Eds. Jusepe de Ribera, lo Spagnoletto, 1591-1652. Fort Worth: Kimbell Art Museum, 1982

• Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso, et al. Jusepe de Ribera, 1591-1652. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992

• Piper, Anson. "Ribera's 'Jacob' and the Tragic Sense of Life. " Hispanica 46.2 (May 1963): 279-282

• Scholz-Hänsel, Michael. Jusepe de Ribera, 1591-1652. Cologne: Könemann, 2000

• Trapier, Elizabeth du Gué. Ribera. New York: The Hispanic Society of America, 1952

• Wind, Barry. "A foul and pestilent congregation:" Images of "freaks" in Baroque art. Brookfield: Ashgate Publishing, 1998