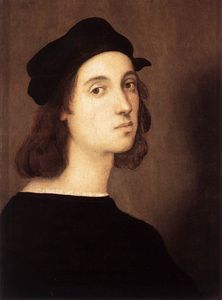

Raphael

- Full Name:

- Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino

- Alternative Names:

- Raphael, Raffaello Santi, Raffaello Sanzio

- Date of Birth:

- 06 Apr 1483

- Date of Death:

- 06 Apr 1520

- Focus:

- Paintings, Architecture, Drawings

- Mediums:

- Oil, Stone, Glass

- Subjects:

- Figure

- Art Movement:

- Renaissance

- Hometown:

- Urbino, Italy

Introduction

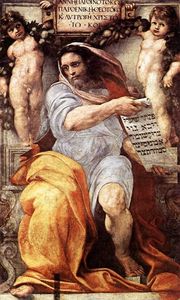

Raphael is acknowledged as one of the greatest artists of all time. An Italian painter, draughtsman and architect, he is, along with Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Titian regarded as one of the foremost figures of the High Renaissance.

Over the course of Raphael's early artistic career he made altarpieces for Citta di Castello and Perugia, and a series of devotional paintings of the Holy Family. After moving to Rome in 1508, Raphael became the star painter of the papal court and achieved acclaim for decorating in fresco the Stanze of the papal apartments. He also executed a number of other smaller paintings in oil and came to run a large workshop, allowing him to diversify, working as an architect and print designer.

Raphael Biography

Early years:

Raphael was born on April 6 1483 to Giovanni Santi and Magia di Battista Ciarla. His father, a painter himself (though of no great renown), was a man of culture who provided instruction in painting and introduced young Raphael to humanistic philosophy at the court of Urbino.

The cultural vitality of the city of Urbino probably helped stimulate the exceptional output of Raphael, who even before the age of 17 displayed a precocious talent.

Upon Raphael's arrival in Perugia in 1495 he was already a 'master', commissioned to work on altarpieces and painting in the workshop of the great Umbrian master Pietro Perugino. Although Raphael learned much from Perugino, by late 1504 he needed other models to work from, and it is clear that his talent demanded that he look beyond Perugia.

Middle years:

Vasari claims that Raphael was drawn to Florence by the accounts of the work that Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo were undertaking there. Florence was his first contact with major artistic civilization and Raphael studied the works of the masters of the High Renaissance.

Among his work between 1505 and 1507 were his famous paintings of Madonna. In his other works during this period - despite drawing directly from da Vinci and Michelangelo in style - Raphael distinguished himself by developing a calmer and more extroverted style that would serve as a popular, universally accessible form of visual communication.

Raphael was called to Rome at the end of 1508 by Pope Julius II, on whom he made a great impression.

Advanced years:

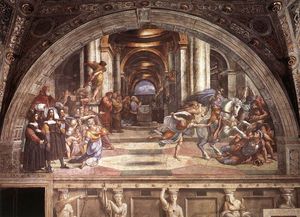

Raphael spent the last 12 years of his life in Rome, consumed in feverish artistic activity with finishing a series of masterpieces. His decoration of the Stanza della Segnatura, where Julius himself lived and worked, with a series of frescoes is perhaps his best-known work.

During this latter part of his life he continued to paint for Leo X following Julius II's death, and explored architecture andalso pursued his interests in archeology and of ancient Greco-Roman sculptures.

In 1515 Leo X appointed him commissioner of antiquities for the city, and by this time he was also virtually in charge of all the papacy's artistic projects in Rome. Raphael's last masterpiece, The Transfiguration, was left unfinished at his death and was completed by his assistant. Dying on his 37th birthday, Raphael's funeral mass was celebrated at the Vatican where The Tranfiguration was placed at the head of the bier, and his body was buried in the Pantheon of Rome.

Raphael Style and Technique

Raphael's style derived from two principal High Renaissance giants: Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. From Leonardo he made use of pyramidal composition and learned to model faces with light from shadow (chiaroscuro); from Michelangelo, Raphael adapted full-bodied, lively figures with the contrapposto pose.

Early years:

Raphael's earliest altarpieces, often painted for chapels, are remarkably close to the style of Perugino. The figures are posed lightly, are meek in gesture and sweet in expression. Many of the details of formal language derive from Perugino, whose own works at the time were indistinguishable from his own. Raphael also imitated Perugino's technique of painting using an oil medium.

Mature period:

Raphael's style and technique changed significantly in Florence and more of his work was completed in pen and ink. His work was often rougher - a means of generating and exploring his ideas as well as defining them.

During this period Raphael also learned the Florentine method of building up a composition in depth with pyramidal figure masses. These figures are grouped as a single unit, but each retains its own individuality and shape. A unity of composition and suppression of inessentials is what distinguishes the works Raphael painted in Florence.

Late style:

Raphael's very large and complex compositions are regarded as the classic art of the High Renaissance. They give a highly idealized depiction of the forms represented, though they are carefully composed to achieve "sprezzatura", which, according to his friend Castiglione, is the certain nonchalance that conceals all artistry. Raphael looked to develop a calmer and more extroverted style (than, say, Michelangelo and Leonardo) that would serve as a popular, universally accessible form of visual communication.

Who or What Influenced Raphael

Raphael's upbringing in Urbino, somewhat of a cultural center during the rule of Duke Federico da Montelfeltro, constituted the basis for all his subsequent learning. Court life in Urbino is where his father taught him to paint, and it was through instruction here that he learnt the basics before going to study under the instruction of Pietro Perugino.

Although Raphael learned much from Perugino's workshop (1495-1504), by late 1504 he needed new models to work from. These he would find in Florence where his principle influences were the works of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. Raphael learned much from Leonardo's lighting techniques, particularly chiaroscuro and sfumato. He was also influenced by the friends he made with several local artists, most obviously Fra Bartommeo, from whom Raphael learnt to replace the fragile grace of Perugino for more gravity and grandeur in his works.

In addition to living artists, Raphael also studied the great Florentine artists of the past, the most significant of these being Donatello.

During his time in Rome, Raphael was engaged in competition, even if only indirectly, with Michelangelo. Raphael was allowed to study the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel before it was complete (much to Michelangelo's chagrin) and imitation of the Chapel's style is strong in his Stanza della Segnatura. After his near-mimicry of Michelangelo in this piece, Raphael drew away from this style, but he had learnt something he never forgot and Michelangelo may never have forgiven.

Raphael Works

Raphael Followers

Julius II:

Julius II was a highly cultured man who surrounded himself with the most illustrious personalities of the Renaissance. He entrusted Bramante with the construction of a new basilica of St. Peter to replace the original 4th-century church; he called upon Michelangelo to execute his tomb and compelled him against his will to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel; and, sensing the genius of Raphael, he charged him with the frescoes in the Stanza della Segnatura.

-

During life:

Raphael left Florence to work in Rome in 1508, summoned by Pope Julius II who would have heard of him through his relatives at the court of Urbino and through his architect Donato Bramante, a compatriot and distant relative of Raphael. However, his being commissioned for works and accepted into the workshop of Perugino at such a young age confirms that he was popularly followed from a young age.

After death:

As a distinguished member of the High Renaissance it can be argued that Raphael has had, albeit indirectly, an influence on nearly every subsequent major artistic movement - all of which can trace their heritage back to this period.

Mannerism (which began soon after Raphael's death) and Baroque took art in a totally different direction to Raphael's qualities, and therefore he was often seen as the ideal model by those who disliked the excesses of Mannerism.

One such group included the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, composed of English painters, poets and critics, whose intention was to reform art by rejecting the mechanistic approach first adopted by the Mannerist artists who followed Raphael and Michelangelo. They believed that the classical poses and compositions of Raphael had been a corrupting influence on the academic teaching of art.

Raphael Critical Reception

During life:

When the last frescoes in the Stanza d'Eliodoro (the Old Testament scenes on the ceiling) were complete in 1514, Raphael was one of the most celebrated artists in Europe. Evidence of the esteem he held at court is verified by the fact that Leo X's chief minister, the papal treasurer Cardinal Bernardo Bibbiena, offered Raphael his niece as a wife.

Even more remarkable is the reason he gave for the hesitation in accepting her hand - the possibility that the Pope would make him a cardinal! Leo X greatly extended the range of work that Raphael undertook in Rome, appointing him one of the architects of St Peter's in succession to Bramante.

After death:

Despite being highly regarded by his contemporaries, Raphael was less influential in his own century than Michelangelo. With Raphael's death, the classic art of the High Renaissance subsided and was taken in a new direction by Mannerism and Baroque.

Despite this, Raphael's compositions have always been admired and studied, and were one of the cornerstones of the training of the Academies of art.

Raphael's greatest period of influence was between the late 17th and late 19th century, where his decorum and balance were lauded. He was universally seen as the best model for history painting.

By the 20th century he was still considered the most famous and loved master of the High Renaissance, but in this respect he has been overtaken by Leonardo and Michelangelo.

Raphael Bibliography

There are countless books written about Raphael and the High Renaissance. Below is a selection of recommended reading on the artist and his works.

• Brown, Clare & Evans, Mark. Raphael: Cartoons and Tapestries for the Sistine Chapel. V & A Publishing 2010

• Chapman, Hugo, et al. Raphael: From Urbino to Rome. National Gallery Company Ltd, 2008

• De Vecchi, Pier Luigi. Raphael. Abbeville Press Inc. , 2003

• Jones, R. Raphael. Yale University Press, 1987

• Talvacchia, Bette. Raphael. Phaidon Press Ltd, 2007

• Whistler, Catherine. Michelangelo and Raphael Drawings. Ashmolean Museum, 1990