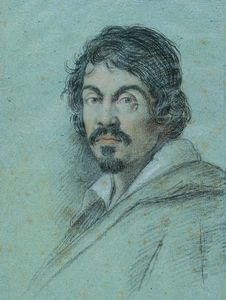

Caravaggio

- Full Name:

- Michelangelo Merisi de Caravaggio

- Date of Birth:

- 29 Sep 1571

- Date of Death:

- 16 Jul 1610

- Focus:

- Paintings

- Art Movement:

- Baroque

- Hometown:

- Milan, Italy

Introduction

Assault. Murder. Consorting with the devil. The notorious succès-de-scandale of the 17th century, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was accused of all of these and more during his tempestuous career. Condemned as the "antichrist of painting," Caravaggio was as controversial for his revolutionary artworks as he was for his infamous temper and lengthy police record.

A notorious painter during his life, following his death Caravaggio was largely forgotten and it wasn't until the 20th century that his key role in the development of Western art was remembered.

Despite a scandalous lifestyle helping to preserve interest in Caravaggio throughout the centuries, in the end, it is the true genius of his works that has won his place in the history of art as well as in the contemporary imagination.

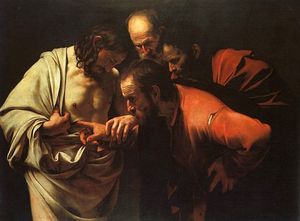

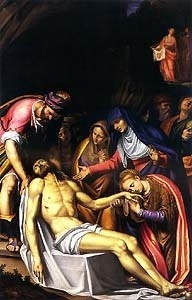

Caravaggio's works constitute some of the most stunning works in the entire history of Western painting. Observing the evolution of his style from his early works (The Fortune Teller, Bacchus and Narcissus) to his major successes (The Calling of Saint Matthew and Doubting Thomas) to his final paintings (David with the Head of Goliath) is like watching the tumultuous ups and downs of his life.

Although chiaroscuro was used long before Caravaggio came onto the art scene it was he who defined the technique and darkened the shadows. The artist's observation of physical and psychological reality strengthened his popularity but caused problems with his religious assignments.

A prolific artist, Caravaggio worked quickly, using live models and using the end of his brush handle to score basic outlines of his work. His preference for working directly onto the canvas was alien to his peers and they accused him of idealizing his figures.

Caravaggio Artistic Context

Caravaggio is a pioneer of the Italian Baroque style that grew out of the Mannerist era. Italian Baroque art was not widely different to Italian Renaissance painting but the color palette was richer and darker and the theme of religion was more popular.

At the end of the 16th century, Caravaggio was fortunate to be working during the Counter Reformation, when virtually the entire city of Rome underwent a construction project as the Catholic Church renovated old churches and constructed new ones in an effort to attract Protestant converts back to the faith. All these new spaces needed lavish amounts of decoration, and artists were all too ready to fill that need.

As well as this, Caravaggio was also exposed to a new interest in scientific naturalism flourishing in northern Italy, due in part to the influx of artworks from northern Europe. Consequently, Caravaggio developed a style of unflinching realism, unprecedented approachability and a direct appeal to the emotions that had no equal among his peers and helped to mould 17th century Italian art.

Caravaggio's influence is evident both directly and indirectly in the paintings of artists such as of Rubens, Bernini, Jusepe de Ribera and Rembrandt. The next generation of artists profoundly influence by Caravaggio were labeled the "Caravaggisti" or "Caravagesques", as well as Tenebrists or "Tenebrosi" ("shadowists"). The secretary of Paul Valéry, Andre Berne-Joffroy, said, "What begins in the work of Caravaggio is, quite simply, modern painting."

In the 1920s art critic Roberto Longhi said of Caravaggio: "Ribera, Vermeer, La Tour and Rembrandt could never have existed without him. And the art of Delacroix, Courbet and Manet would have been utterly different".

Bernard Berenson agreed: "With the exception of Michelangelo, no other Italian painter exercised so great an influence".

Caravaggio Biography

Caravaggio takes his name from the town in which he was born in 1571 to a majordomo in a region of Italy known as Lombardy. The artist was born during the politically and spiritually tumultuous time of the Counter-Reformation, when the Catholic church was trying to regroup after the Protestant Reformation, and this historical context had an indelible impact on his personal and artistic development.

Caravaggio's father died from the plague when the artist was only 6 years old. At age 13, Caravaggio was apprenticed to Milanese artist Peterzano, who instructed the young man in the basics of the craft, such as preparing pigments, mixing colors, and the rudiments of drawing, anatomy, and perspective. The unprecedented naturalism that marked Caravaggio's mature style most likely had its roots here: there was a markedly naturalist trend in the art of the Lombardy region, and art historian Helen Langdon suggests that Peterzano may have encouraged the young Caravaggio to study from nature.

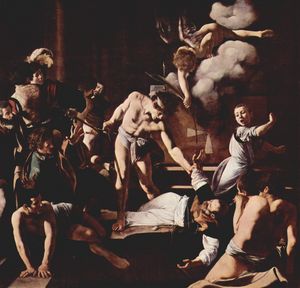

Still a young man, Caravaggio moved to Rome in 1592, where he spent his first years in utter poverty, painting for the open market. His career got a much-needed jumpstart when the influential art lover Cardinal del Monte took the young artist under his wing and became his first steady patron. Thanks to Cardinal del Monte's influence, at age 24 Caravaggio was given his first major public commission of three paintings in the Contarelli Chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi. This triptych of scenes from the life of Saint Matthew constitute a sort of first manifesto of naturalism, and attracted massive public attention as well as public and critical outcry due to their unprecedented naturalism and dramatic, smoky chiaroscuro (contrast between light and dark).

Caravaggio attracted an overwhelming share of virulent critics and enemies: socially, he was a belligerent, rude, violent and finally homicidal hot head, while artistically, he was a daring rule breaker who thwarted the classical rules of art. At the same time, however, his ability to depict religious scenes with an unprecedented approachability and the most human of feelings and sentiment provided invaluable inspiration for artists throughout the ages, including such masters as Rubens, Velasquez and Rembrandt.

Caravaggio Style and Technique

Caravaggio's works were so controversial in their own time (and for centuries after) for their utterly innovative, revolutionary style. The intense, dramatic contrasts of light and dark, resolute realism, meticulous attention to naturalistic detail and approachable, life-like models set Caravaggio's paintings apart from all the masters that preceded him.

Caravaggio's first known paintings date from his arrival in Rome in 1592. During these first years, he was completely destitute and painted small genre scenes, self-portraits and still-lifes to earn money on the open market.

From 1595 onwards, Caravaggio's career was boosted when the influential Cardinal del Monte welcomed him into his court. The young artist executed paintings for the Cardinal and took advantage of his connections to garner prime commissions from Rome's wealthiest patrons and collectors.

The artist's compositions became more complex and contained various characters. Additionally Caravaggio's pictures became darker during this time.

In 1599, Cardinal del Monte used his influence to get Caravaggio his first major commission: the decoration of the Contarelli Chapel. These three paintings showing scenes from the life of St. Matthew constituted Caravaggio's triumphant (and controversial) bursting onto the Roman art scene.

The commissions came pouring in after 1600, despite Caravaggio's difficult temper, problems with the law, and soaring prices. This stage in his career saw he artist creating many religious works with larger and more complex arrangements. The artist had clearly solved his early compositional problems.

In some respects, Caravaggio's art was in keeping with the spirit of the Counter-Reformation: after the artificial decadence of Mannerism, the Church was seeking a simpler, more direct art that would have a maximum effect on the emotions.

Caravaggio's art was certainly natural and direct, but to an extreme that made the Church uncomfortable, as the artist portrayed sacred religious personages as real, common people, complete with bare feet and dirt under their fingernails.

In addition to his radical naturalism, Caravaggio's other major innovation was his intense, tenebristic chiaroscuro, which lent a dramatic, theatrical air to his paintings, setting the tone for the high drama of the Italian Baroque.

In 1606, Caravaggio had to flee Rome with a price on his head after committing a murder. During this time of intense fear and personal trauma, Caravaggio's paintings reached the ultimate in darkness and despair. Focusing on religious subjects and portraits his works were grim, somber and unsettling.

Who or What Influenced Caravaggio

Caravaggio was famous for scorning the work of other artists, including the masters of the Renaissance and antiquity. The confident rebel claimed that he had surpassed all other artists and painted purely from nature. A closer look at Caravaggio's paintings, however, shows that not even he was immune to stylistic influence.

Michelangelo:

Even Caravaggio couldn't resist drawing inspiration from the lesson of the great Renaissance master, Michelangelo. Caravaggio would have had ample opportunity to observe Michelangelo's works all across Rome, especially in the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo's influence is clear in Caravaggio's The Calling of Saint Matthew, where Christ's hand is an exact reflection of the hand of Adam.

Leonardo da Vinci:

No succeeding Italian artist could paint without some evidence of da Vinci in his works, whether it was intended or not.

One example is Caravaggio's Medusa which was commissioned by Cardinal del Monte, who worked for the Medici family in Rome. According to biographer Vasari, in a document from 1568 da Vinci also created a Medusa shield that was in the Grand Duke's collection. If this is indeed the case, del Monte would certainly have known about it and instructed the young artist to follow the master.

The other widely cited example of da Vinci's influence is apparent in Caravaggio's Judith Beheading Holofernes. Here, the grotesquely intense face of the old crone holding the bag for Holofernes's head is undeniably evocative of da Vinci's caricatures.

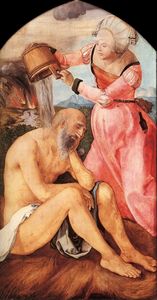

Dürer:

Although a native of far away Germany, the influence of this genius of the Renaissance extended as far as Italy. Caravaggio could have known Dürer's works thanks to the freely circulating copies of his engravings and prints.

Northern art:

Especially in his early works, Caravaggio reveals a remarkable skill for still-lifes, particularly fruits and flowers, as is evident in works like Basket of Fruit, Bacchus and The Lute Player. This subject was imported to Italy from the sumptuous pictures of fruits and flowers that abounded in Dutch and Flemish art, notably in the works of artists like Pieter Aertsen and Joachim Beuckelaer.

These works became popular in northern Italy at the end of the 16th century and could have been known by Caravaggio through engravings.

Caravaggio Works

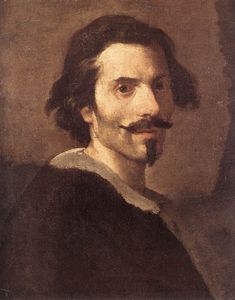

Caravaggio Followers

While his style shocked the artistic elite of the day, Caravaggio's paintings inspired the young, up-and-coming artists of Rome in equal measure. These artists came to be known as the Caravaggisti and were spread all over Europe, from Rome and Naples to the Netherlands and France. Some have even suggested that such great masters as Rubens and Velazquez were also influenced by this genius of the Italian Baroque.

The Roman Caravaggisti:

Notably including Orazio Gentileschi, his daughter Artemesia Gentileschi and Bartolomeo Manfredi, these artists were especially active in the years after Caravaggio's death in 1610.

The Caravaggisti did depart from the style of the master in some significant ways, however. While the Gentileschis stayed relatively close to the sober spirit of Caravaggio's works, other Caravaggisti like Manfedi strayed into genre subjects with extravagant, buffoonish characters, the likes of which Caravaggio himself would never have portrayed.

Caravaggism continued into the 1620s, when the movement died out as the more classicizing style of Annibale Carracci came to reign supreme.

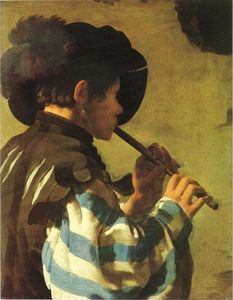

The Utrecht Caravaggisti:

When this set of young artists (including Heindrich Ter Bruggen, Gerrit von Honthorst and Dirch van Baburen) made their pilgrimage to this artistic Mecca in the first years of the 17th century, they came face-to-face with Caravaggio's masterpieces and forged the Utrecht Caravaggisti.

In general, the works of the Utrecht Caravaggisti are far lighter than their Roman counterparts, literally and figuratively. These artists take the same themes found in Caravaggio's works and push them into the realm of churlish humor, with more overtly moralizing intentions.

The French Caravaggisti:

The French interpretations of Caravaggio are perhaps the strangest. Simon Vouet's interpretation of The Fortune Teller, for example, is a semi-ridiculous, lewd version of Caravaggio's model, retaining only the Italian master's theme and intense chiaroscuro.

The thematic and stylistic affinities between the works of Georges de la Tour and Caravaggio are undeniable. De la Tour's Fortune Teller, for example, has a composition similar to the Caravaggio painting, and furthermore shares the neutral background and external light source coming from the upper left side of the picture plane. On the other hand, the bizarre clothing, even stranger, geometricized faces, stiff postures and an overall eeriness are all la Tour's own.

Caravaggio's famous chiaroscuro is what is most evident in la Tour's oeuvre.

Fellow Spanish Baroque painter Francisco de Zurbarán also seems to have something of Caravaggio in his works, in their intense chiaroscuro, limited, sober palette, and simple, often single-figure compositions.

Caravaggio Critical Reception

Michelangelo Merisi de Caravaggio is the original succès-de-scandale, an artist whose smolderingly passionate, tumultuous personal life is overshadowed only by his revolutionary and breathtaking œuvre. With his unprecedented naturalism and unerring talent for rendering the play of light and dark, Caravaggio revolutionized Italian art and blazed the way for the seventeenth century Italian Baroque.

The history of Caravaggio's critical reception is almost as fascinating as the life of the artist itself.

Condemned as the "antichrist of painting," Caravaggio's scandalous life kept him in the public eye but his real talent earned him his place in the history of art. A revolutionary painter, Caravaggio ignored the rules that artists from the previous century had followed and instead developed a love of realism and his emotional directness was unrivalled.

Caravaggio played a key role in defining 17th century Italian art and was a successful painter during his life. Following his death he was largely forgotten but renewed interests in his work came about in the 20th century when emerging artists were adopting his techniques and imitating his style. Caravaggism had profound effects on the art world and artists that were directly and indirectly influenced by Caravaggio include Rubens, Hals, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Velazquez and Bernini.

Contemporary biographers as well as public records provide a fascinating portrait of this often disturbed artist. One notice from 1604 describes a Caravaggio who "after a fortnight's work... will swagger about for a month or two with a sword at his side and a servant following him, from one ball-court to the next, ever ready to engage in a fight or an argument, so that it is most awkward to get along with him."

Caravaggio is undoubtedly one of the most enigmatic, intriguing, and rebellious personalities in the history of art.

Caravaggio Bibliography

To read more about Caravaggio and his works please refer to the recommended reading list below.

• Bernedetti, Sergio. Caravaggio: The master revealed. Dublin: The National Gallery of Ireland, 1993

• Freedberg, S. J. Circa 1600:A revolution in the style of Italian painting. Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press, 1983

• Friedlander, Walter. Caravaggio Studies. New York: Schocken Books, 1969

• Gilbert, Creighton. Caravaggio: his two Cardinals. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995

• Hibbard, Howard. Caravaggio. New York: Harper and Row, 1983

• Hinks, R. P. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio: His life, his legend, his works. London: Faber & Faber, 1953

• Langdon, Helen. Caravaggio: A life. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1999

• Mancini, Giulio, Giovanni Baglione, and Giovanni Bellori. Lives of Caravaggio. London: Pallas Athene, 2005

• Moir, Alfred. Caravaggio. New York: H. N. Abrams, 1989

• Varriano, John. Caravaggio: the art of realism. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006