Gian Lorenzo Bernini

- Short Name:

- Bernini

- Alternative Names:

- Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini, Gianlorenzo Bernini

- Date of Birth:

- 07 Dec 1598

- Date of Death:

- 28 Nov 1680

- Focus:

- Paintings, Sculpture, Architecture

- Mediums:

- Oil, Mixed, Stone

- Subjects:

- Figure

- Art Movement:

- Baroque

- Hometown:

- Naples, Italy

- Architecture:

- Cathedra PetriSaint Peter's baldachinSaint Peter's Square & ColonnadePalazzo Barberini

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini Page's Content

- Introduction

- Artistic Context

- Biography

- Style and Technique

- Works

- Followers

- Critical Reception

- Bibliography

Introduction

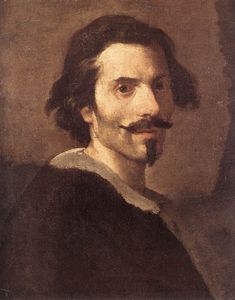

The world of art would never be the same after the arrival of star sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini. During a lifetime marked by the giddiest of heights (including knighthood and close friendships with popes and royalty) as well as the most dismal of lows (dramatic professional failures and a homicidally tumultuous love life), Bernini forever changed the face of the city of Rome and single-handedly launched the style that would dominate seventeenth-century Italian sculpture.

Heralded by many in his lifetime as the heir of Michelangelo, Gian Lorenzo Bernini worked primarily in a steady stream of critical success. As one of the foremost architects of the Baroque style, naturally Bernini had his fair share of devoted followers. From contemporaries who worked directly under him or competed with him for commissions, up to modern artists who looked to his use of emotional multimedia design for inspiration, a multitude of artists can thank Bernini for the development of their own styles.

However in the backlash against the Baroque that occurred with the advent of Neoclassicism, the accolades faded into harsher criticisms. Bernini's reputation was only restored in the second half of the twentieth century and today he is recognized as one of the most spectacular geniuses in Western art history.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini Artistic Context

Bernini's career spans the height of the Italian Baroque. Baroque art is profoundly tied to the religious and political context of 16th and 17th century Italy: after the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church launched its own Counter-Reformation to reaffirm its power and attract more followers to the faith. In order to do so, the leaders of the church called for artistic spectacles that would captivate the attention, stimulate the senses, and elevate the soul. Consequently, Baroque art tends to the massive, dramatic, and theatrical.

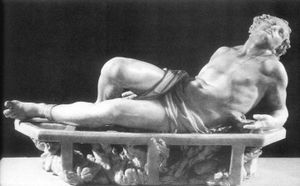

Bernini's sculptures are recognizable for their engaging drama, dynamism, tension, texture, and naturalism. The last two criteria (texture and naturalism) are perhaps the most particular to Bernini: no one can make stone convey soft skin, curling hair, or crinkling fabrics the way Bernini can. His sculptures are also unique for the careful attention he pays to the effects of light and shadow, effects which are traditionally more important to the painter than the sculptor.

Many elements of Bernini's style reveal the influence of Mannerist and Hellenistic sculpture.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini Biography

Early Years:

Practically since his birth in Naples in 1598, Bernini's sculptor father Pietro was determined to pass his art on to his son. At the age of 8 Gian Lorenzo was taken by his father to Rome, where they were awarded an audience with Pope Paul V who, according to legend, declared the boy the next Michelangelo.

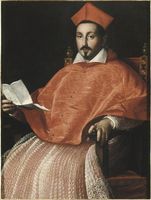

Bernini had already established himself as a prodigious artist by his late teens, when he received his first major commissions from rapacious art lover Cardinal Scipione Borghese. The early works executed for the Cardinal won Bernini such acclaim that praise and accolades began to pour in. In 1621, Bernini was knighted, and in 1629, he was named the Official Architect of Saint Peters, one of the highest honors an artist could wish for. The artist frequented papal and royal circles, and was fervently admired even outside of Italy.

Middle Years:

Things took a turn for the worse when a series of events in his personal and professional life led the artist to attempt to murder his own brother and brutally mutilated the face of his married lover in 1640, after discovering that the two were also having an affair. Even worse, in 1646, the bell tower Bernini created for the façade of St. Peter's had to be demolished after it developed worrisome cracks, and the shame of this failure proved almost too much for the artist to bear: contemporary sources say Bernini took to his bed and fasted almost to the point of death.

Advanced Years:

The wild success of The Ecstasy of Saint Theresa immediately revived Bernini's career, and the artist experienced continuing success and popularity until his death in 1680.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini Style and Technique

Both due to the religious fervor of Bernini himself and the fact that the majority of his commissions were given by religious figures, a high percentage of his work was religious by theme. However, perhaps due to the influence of the classical collections of Scipione Borghese, one of his first patrons, Bernini also had a persistent interest in mythological figures. Additionally, due to the patronage that he was driven by, Bernini executed a series of portraits, both in painted forms and sculpted busts.

Defining Characteristics:

Composition:

Drawing from the influences of Mannerist artists, Bernini created swirling, dynamic compositions in his sculptures that were meant to be viewed from all directions, inviting the viewer to be a part of the scene.

Dramatic Intent:

Bernini is famous for portraying the most poignant moment in a story and for communicating that event in the most dramatic way possible, by means of exuberant movement, emotive facial expressions, and feats of technical mastery.

Texture:

Whether it be billowing swirls of fabric, luxuriously curling locks of hair, meticulously veined leaves, the roughness of tree bark, or the supple softness of skin, Bernini paid texture a great deal of attention in his sculptural works.

Naturalism:

Although his figures are always somewhat idealized, like a perfected version of reality, Bernini manages to bestow them with individualized features and imbue them with human emotion, and never neglects the careful details that help to bring his sculptures to life.

Movement:

From the spiraling columns of the Baldachin that draw the eye heavenward to the flutters of the fabric in his portrait busts, all of his works give the sense of being a snapped moment of stillness in the frenzy of motion.

Hallmarks:

Through the combination of sculpture, architecture and painting he created a new idea of what an artwork could encompass.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini Works

Gian Lorenzo Bernini Followers

Though the Baroque and Bernini along with it went out of fashion for a long period of time, in the 20th century Bernini was "rediscovered" as a true master of realism and emotion, earning a renewed respect and influence on a new generation of artists, which continues up to this day.

Tadao Ando:

Particularly in Bernini's architectural works one can say he was quite ahead of his time, combining painting, sculpture and the architectural piece itself into one multimedia, multisensory work that was intended to play upon the senses of the spectator. This conception of architecture can be seen as an influence upon modern architects such as Tadao Ando, who is known for his own works that explore the idea of architecture as more of an artistic endeavor.

Using natural lighting effects and geometry, Ando strives for the same all-encompassing emotional effect that Bernini did in his works such as the Ecstasy of St. Teresa.

Lee Bontecou:

One of the first female artists to achieve major recognition in the 1960's, Bontecou's sculpture takes a cue from Bernini in its ornate details, giving a modern spin on the Baroque. Created from multimedia materials, ranging from wire and mesh to plastic; her works take on an emotional depth be they of abstract or realistic subject matter.

Rococo Followers:

Rococo artists took the Baroque gilt-plated ball and ran with it, using the tradition set by artists such as Bernini of theatrical ornamentation and applying it to their own painting, architecture, and sculpture.

Francesco Queirolo:

Impressed by Bernini's virtuosity in depicting various textures in sculpture, Queirolo took the realism to dizzying new heights.

Baroque Followers:

Many artists in Italy at the time either studied under or emulated Bernini's style, though none matched his individual brilliance and unique ability. Saturating the market with overly-complicated sculptures, a backlash was inevitable, leading to the restrained values of neoclassicism.

Giovanni Battista Foggini:

Born in Florence but trained in Rome in the 1670s, Foggini displayed a profound influence by the Baroque style pioneered by Bernini. In his reliefs for chapels throughout the city, the same fluidity of movement and attention to ornate detail is seen that is clearly a byproduct of the Bernini influence.

Alessandro Algardi:

Another prominent baroque sculptor working at the same time as Bernini was Alessandro Algardi. Exhibiting the same emotional style of sculpting, with an intensity of dramatic action in facial expressions and tension in physical poses, Algardi's compositions were packed with the same naturalism and obsessive attention to detail. Unfortunately he struggled throughout the last few decades of his life to measure up to Bernini, who received the majority of important commissions from the favors of the Borghese and Barberini families.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini Critical Reception

During his lifetime, Bernini was the superstar of the art world, with no shortage of commissions, much to the annoyance of other artists and imitators. It was said that he achieved a new conception of reality through his intense detail and ornamentation, and was regarded as the "new Michelangelo". He was one of the most admired and sought-after artists, with the highest of reputations. Italian and French contemporaries praised him with detailed biographies, sure of the genius in their midst.

Yet, with the rise of Neoclassicism in the late 1700s-1800s there was a definite anti-Baroque sentiment in the air, with critics of the era lashing out against the perceived decadence, overwrought eroticism, and what was deemed insincere emotion of the movement. Neoclassicism is founded on the tenets of purity and the return to the ideals of form and repression of emotion that are exemplified in the works of Ancient Greece and Rome.

Art history as it is known today was fundamentally shaped by the German historian and archaeologist Winckelmann. His significant bias against the Baroque in general and Bernini in particular was transmitted to subsequent generations of art historians.

English artist and thinker Sir Joshua Reynolds accused Bernini of being a "cheap sorcerer" who misled and tricked the viewer with his technical mastery, and "betrayed" the intrinsic qualities of the stone by making it appear like skin, cloth, or leaves. Reynolds felt that such illusionistic effects were better suited to painting than sculpture.

Poet, art critic, influential thinker, and fellow Englishman John Ruskin described Bernini's works as devoid of religious feeling and coarsely sensual. Of the Ecstasy of Saint Theresa, he said it was "impossible for false taste and base feeling to sink lower."

It wasn't until the second half of the 20th century that important art historians like Howard Hibbard and Donald Posner re-examined the Baroque period and the critical tide turned once again, this time in Bernini's favor.

The influential art historian Rudolf Wittkower was perhaps most responsible for reviving interest in the works of Bernini. With the publication in 1955 of Bernini: The Sculptor of the Baroque Era, he made a strong case for the influence and artistic merit of the artist who had been ridiculed and even forgotten during the previous few centuries. This sparked a newfound interest in Bernini, with a multitude of exhibitions, lectures, and publications being generated about Bernini and his groundbreaking sculpture of the Baroque. Tourism to Rome has only intensified, with his works being must-sees on any Roman holiday.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini Bibliography

Some of the most important academic resources on Bernini and his works include the following;

• Bauer, George, ed. Bernini in Perspective. Prentice-Hall, 1976

• Borsi, Franco. Bernini. Trans. Robert Erich Wolf. Rizzoli, 1984

• Gould, Cecil. Bernini in France: An Episode in Seventeenth-Century History. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1981

• Hibbard, Howard. Bernini. Penguin Books, 1965

• Lavin, Irving. Bernini and the Unity of the Visual Arts. For Pierpont Morgan Library by Oxford University Press, 1980

• Magnuson, Torgil. Rome in the Age of Bernini. Almqvist & Wiksell International

• Morissey, J. P. The Genius in the Design: Bernini, Borromini, and the Rivalry that Transformed Rome. Duckworth, 2005

• Wittkower, Rudolf. Gian Lorenzo Bernini: The Sculptor of the Roman Baroque. Cornell University Press, 1981