Diego Velazquez

- Full Name:

- Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez

- Short Name:

- Velázquez

- Date of Birth:

- 06 Jun 1599

- Date of Death:

- 06 Aug 1660

- Focus:

- Paintings

- Mediums:

- Oil, Other

- Subjects:

- Figure, Scenery

- Art Movement:

- Baroque

- Hometown:

- Seville, Spain

Introduction

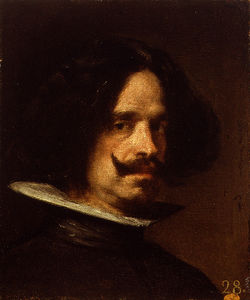

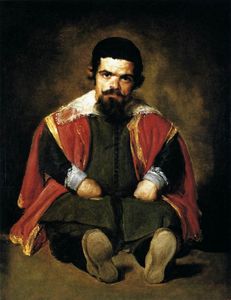

Diego Velázquez was a prolific artist who went on to become court painter for King Philip IV. Velázquez set himself apart from his contemporaries with his individual style and eye-catching portraits. During his career the Spanish artist created many portraits of the Spanish royal family, powerful European figures, and members of the lower class, as well as producing many genre paintings. His painting Las Meninas is regarded as his masterpiece.

It was in the nineteenth century that Sir David Wilkie commented from Madrid that he saw something special in the paintings of Velázquez and noted a resemblance between these and the British school of portrait painters, particularly Henry Raeburn.

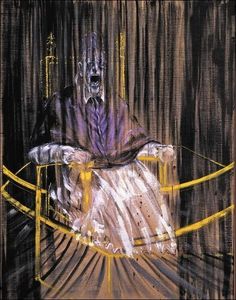

Velázquez work set the precedent for early nineteenth century realist and impressionist painters, especially Édouard Manet. Since then, Velázquez has continued to influence emerging artists as diverse as Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, and Anglo-Irish painter Francis Bacon. Such artists have demonstrated their love for the works of Velázquez by recreating some of his most noted paintings.

Diego Velázquez was hailed a father of the Spanish school of art and is one of the greatest artists that ever lived. Although influenced by the Italian schools and his peers he developed his own principles of art and his technique and unique style earned him a legion of fans and followers. It could be said that Velázquez had a greater influence on European art than any other painter.

Diego Velazquez Artistic Context

Diego RodrÍguez de Silva y Velázquez was born into a society of paradox: Spain was simultaneously undergoing one of the most dramatic economic and political declines of any nation in European history, and unprecedentedly fertile, creative bursts of artistic activity.

In Velázquez's hometown of Seville (home to literary luminaries Cervantes and Lope de Vega) in particular, circles of Humanist learning, arts and letters and philosophy all flourished, constituting a particularly fecund environment for a young artist.

On the other hand, Velázquez's chosen profession would become a significant obstacle in the artist's personal agenda. Spanish society was obsessed with nobility, and unlike in Italy, the visual arts were emphatically not equated with noble pursuits like literature or philosophy.

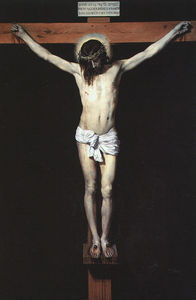

Artists were seen as essentially vulgar craftsman who worked for a living with their hands, just like blacksmiths or tailors. Making matters even more complicated, the Catholic church exercised almost total power over the arts in Spain, dictating everything from subject to composition, meaning that artists had very little room to experiment or grow. Velázquez was thus fated to struggle from the very incipience of his career.

Diego Velazquez Biography

Early years:

Velázquez was born in Seville to a middle-class family and received an exceptional academic education in the arts and sciences. At the age of eleven he went to study with his enormously influential painter Francisco Pacheco.

After five years of studying under Pacheco, the older artist consented to giving Velázquez his daughter's hand in marriage. Velázquez married Juana Pacheco in 1618, at the ripe old age of nineteen and the couple had two daughters together.

At the beginning of April, 1622, the young artist set off for Madrid in the hopes of charming his way into the court. Thanks to some strings pulled by the king's right-hand man Olivares, in August 1623 Velázquez painted the portrait of King Philip IV. The king was so enamored with the result, he immediately named Velázquez his sole and unique portrait painter.

In 1628, Peter Paul Rubens descended on the Spanish court on a diplomatic mission. Rubens proved to be an enormous influence, particularly in suggesting that Velázquez make the pilgrimage to Italy which was inspirational in Velázquez's later career.

Middle Years:

The 1630s were Velázquez's most fruitful years, artistically speaking, and represent an intensification of Velázquez's lust for glory, recognition and, most importantly, power.

Throughout this decade Velázquez was also nominated to various new positions at the court, which involved responsibilities in decorating the apartment and maintaining the royal collection. By maintaining close ties to both the pope and king, Velázquez managed to accrue an unusual amount of power and influence at court, especially for a mere artist.

Finally, by the 6 June 1658 (the year of his one surviving daughter's death), Velázquez was nominated to the Order of Santiago. Amazingly, the artist was turned down two times by the order, necessitating two separate dispensations from the pope. The Order finally gave in (admittedly, under heavy pressure from both the king and pope) was a major step in recognizing the arts as elevated above artisanal labor.

Advanced Years:

In 1660, the devastating war between France and Spain finally ended and the countries were united with the marriage of the infant Maria Theresa and the King of France, Louis XIV. As part of his official duties, Velázquez travelled to the French-Spanish border to the Island of Pheasants in order to execute the decoration and "scenic display."

Velázquez returned to Madrid on June 26, only to be struck with a fatal fever on July 31. Velázquez died on the 6th of August 1660.

Diego Velazquez Style and Technique

Velázquez's paintings are refreshingly simple, direct, and frank both in tone and execution. Stylistically, then, Velázquez is closer to Caravaggio or an early Annibale Carracci than he is to more flamboyant artists like Rubens or Bernini.

Velázquez's style can be characterized by its simplicity, dignity, restrained palette, and loose, impressionistic brushstroke.

Early Style:

Velázquez paints exactly what he sees, exquisitely rendering textures and fabrics without the need for added adornment or ornamentation. Like the painters of northern Italy, Velázquez's style is marked by a direct, confrontational naturalism. This is especially evident in the stunning still-life elements that abound in these early works, especially Old Woman Cooking Eggs, and The Waterseller of Seville.

Velázquez employed a dark, restrained, earthy palette throughout his entire career, but the early paintings in particular are notable for their sober, terracotta tones. One of the most unique aspects of Velázquez's style throughout his career is his unusually dignified, objective portrayal of even the lowliest of subjects whom he depicted with an innate dignity and humanity.

Mature Style:

Art historians usually divide Velázquez's style into two periods: pre-Italy, and post-Italy. Visiting the Italian masters at the end of the 1620s certainly had an enormous impact on Velázquez's art, although it is difficult (if not impossible) to discern any precise influences from a particular artist.

In general, however, Velázquez learned many lessons from the Venetians, especially from their rendering of fabrics and materials.

Velázquez's technique in the rendering of fabrics was far different from that of his contemporaries or predecessors, however. Velázquez eschewed careful, precise brushwork and instead employed loose, impressionistic flurries of paint that create an astounding, realistic image from afar, but which upon closer inspection appear almost abstract.

Technique:

Velázquez is often described as a kind of forerunner of Impressionism and indeed Impressionist painters like Manet adored this artist of the Spanish Baroque, and were particularly inspired by his unusually fluid, free brushstroke. Note, for example, the surprisingly abstract depiction of the artist's hand and palette in Las Meninas, or the similarly abstract treatment of the little dog's body in the portrait of the Infante Felipe Próspero.

In passages such as these, Velázquez's brushstroke is loose, fluid, and utterly present on the canvas, as if in defiance of the picture's very realism. Velázquez disdains to delineate precise contours, instead creating form out of pure color and light.

Despite this abstract style, however, Velázquez still manages to convey a sense of utter realism and liveliness.

Who or What Influenced Diego Velazquez

Velázquez is a fascinating case, for his style is utterly unique. Although encounters with such dynamic forces as Rubens or the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance certainly inspired Velázquez into a creative fury, they did not particularly influence his style.

In general, Velázquez's style is uniquely Spanish, although a few stylistic influences can be cited with some certainty;

Caravaggio:

Velázquez's oeuvre bears remarkable similarities to Caravaggio's painting in a number of ways. The two artists share an interest in genre subjects and in painting people from the street, an intense naturalism, a sober palette and dramatic effects of light and dark. Even in terms of composition, the work of the two artists bears eerie similarities.

Caravaggio's influence on Velázquez extends throughout the Spanish artist's entire oeuvre. It is not certain, of course, that Velázquez could have had any direct knowledge of Caravaggio before he travelled to Italy for the first time in 1628, but the northern Italian influence was strong in Seville during Velázquez's most formative years (contemporary Ribera was similarly marked by Caravaggio's style), and the stylistic similarities between the two artists are undeniable.

The Venetians:

Like other Baroque artists such as Annibale Carracci, Velázquez was tremendously impressed with painters of the Venetian Renaissance such as Tintoretto, Titian and Veronese. These artists influenced Velázquez most notably in his rendering of color (note that Velázquez's palette lightens and somewhat after his trip to Italy) and light.

Titian's portraits of Pope Paul III most likely also constituted an influence for Velázquez's Pope Innocent X.

Diego Velazquez Works

Diego Velazquez Followers

17th Century Spain:

Juan Bautista Martinez del Mazo:

This relatively mediocre Baroque artist was lucky enough to marry Velázquez's one surviving daughter. Many of Velázquez's lesser quality works were long attributed to Mazo and the younger artist conformed faithfully to his master's model, especially in portraiture.

Mazo is the rare example of a 17th century Spanish artist already evidencing Velázquez's influence.

17th Century Italy:

The Italians were thrilled with his Portrait of Innocent X and Velázquez's style quickly became popular amongst such important artists of the Italian Baroque as Bernini. Particularly influential was Velázquez's portrait style.

The 19th Century:

During the Peninsular War (1808-14), some of the artist's paintings were brought to northern Europe. Throughout the rest of the century the nation progressively began to open up to the rest of the continent.

Francisco Goya:

Goya executed several prints based on Velázquez's paintings, and learned several lessons from the master artist, particularly in terms of technique, and how to depict subtle gradations of color and glowing highlights.

Édouard Manet and the Impressionists:

Velázquez's influence was most significantly felt in Manet's portraiture, but another significant element of Velázquez' style also had a huge impact on Manet and, later, the Impressionists: Velázquez's loose, unabashedly free and expressive brushstroke.

James Abbott McNeil Whistler:

Whistler's use of bravura brushwork, and his typical compositional technique of placing his subjects against a flat, neutral background (typically gray or brown) is deeply indebted to Velázquez. Whistler's painting The Artist in His Studio was intended to be a modern interpretation of Velázquez's Las Meninas.

John Singer Sargent:

This expatriate American painter is, like Velázquez, primarily known for his stunning portraits. Sargent was influenced not only by Velázquez's portrait style (an informal grouping of sitters against a relatively neutral background), but also by his technique of painting "alla prima," that is, painting directly on the canvas without extensive preliminary under drawing and sketches.

The 20th Century:

Artists from a wide range of movements and styles have consciously picked up on Velázquez's major themes, including Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Richard Hamilton, and Francis Bacon, only to name a few.

Diego Velazquez Critical Reception

While most artists of the Baroque period suffered from a serious drop in critical opinion during the 18th century, eventually fading into oblivion until being rediscovered in the 1950s, Velázquez took an alternate route. Because of Spain's political situation, the nation was more or less isolated from the rest of Europe during the heights of Neoclassicism, meaning that Velázquez's reputation was safe from the hands of Baroque-haters like Wincklemann, who managed to destroy the reputation of such artists as Caravaggio, Carracci and Bernini.

By the time Spain opened up to the rest of Europe in the beginning of the 19th century, the world was ready for Velázquez, and critics and artists alike haven't ceased singing the master painter's praises.

The 19th Century:

Notoriously cantankerous, Victorian art critic John Ruskin gleefully eviscerated other Baroque artists. Velázquez, however, he actually liked! The crotchety critic is quoted as having stated: "everything Velázquez does may be taken as absolutely right by the student. "

And Ruskin wasn't alone: 19th century England and France were agog with admiration for the Spanish artist. Napoleon's conquest in the early years of the century actually brought some of the artist's works back to France, where all things Spanish became the hottest trend of the moment.

By mid-century the Impressionists (including Manet, Renoir and Degas) were picking up on Velázquez's style and themes, and the artist's reputation was assured for years to come.

The 20th Century:

Velázquez has not ceased to be a remarkably fecund source of inspiration for art critics and art historians up until the present day, nor has his reputation as one of the greatest painters of all time been dimmed.

In the twentieth century, some of the most important authors on Velázquez have included Jonathan Brown, Leo Steinberg, philosopher Michel Foucault, and Svetlana Alpers, only to name a few. These scholars have delved into previously obscure depths in the study of Velázquez's biography, techniques, and iconography, interpreting Velázquez's paintings with new methodologies (like phenomenology or Marxism).

Diego Velazquez Bibliography

The following list offers some of the best sources of further reading on Velázquez and his works.

• Brown, Dale. The World of Velázquez: 1599-1660. Time-Life Books, 1969

• Brown, Jonathan. Velázquez, Painter and Courtier. Yale University Press, 1986

• Carr, Dawson, et al. Velázquez. Yale University Press, 2006

• Davies, David, et al. Velázquez in Seville. National Galleries of Scotland, 1996

• Harris, Enriqueta. Velázquez. Phaidon, 1982

• Kahr, Madlyn Millner. Velázquez: the art of painting. Harper and Row, 1976

• López-Rey, José. Velázquez: A catalogue raisonné of his œuvre. Faber and Faber, 1963

• Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso, et al. Velázquez. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989

• Wolf, Norbert. Diego Velázquez, 1599-1660: the face of Spain. Taschen, 1998

• Wind, Barry. Velázquez's Bodegones: A study in 17th century Spanish genre painting. Fairfax: George Mason University Press, 1987