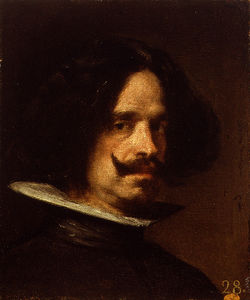

Diego Velazquez Biography

- Full Name:

- Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez

- Short Name:

- Velázquez

- Date of Birth:

- 06 Jun 1599

- Date of Death:

- 06 Aug 1660

- Focus:

- Paintings

- Mediums:

- Oil, Other

- Subjects:

- Figure, Scenery

- Art Movement:

- Baroque

- Hometown:

- Seville, Spain

- Diego Velazquez Biography Page's Content

- Introduction

- Early Years

- Middle Years

- Advanced Years

Introduction

The biography of Diego Velázquez is the story of an artist on a quest for fame, glory, and power. Born into a middle class family but raised with illusions of grandeur, Velázquez's life was devoted not only to becoming the best painter in Spain, but to climbing the social ladder up to the giddiest of heights.

Diego Velazquez Early Years

Velázquez was born in Seville to father Juan Rodriquez de Silva, a lawyer of Portuguese-Jewish descent, and mother Jerónima Velázquez, a member of the hidalgo class (a minor form of aristocracy).

The Velázquez family was in the same situation as most of Spanish society: although the family had illusions of grandeur and pretentions to nobility, their tainted, Jewish ancestry and minor social status meant that they were nothing more than middle-class dreamers.

The very fact that they would allow their oldest son to pursue as lowly a profession as painting speaks to the fact that the family was not as noble as they would have the rest of Spain believe.

Nonetheless, the family was at least wealthy enough to offer Velázquez a most exceptional academic education in the arts and sciences, something rare in a nation with only twenty percent literacy. One can imagine, then, that from an early age, Velázquez was instilled with a more than elevated sense of self-worth and entitlement.

This self-pride would only become heightened once the eleven-year-old boy went to study with his enormously influential (though artistically mediocre) painter Francisco Pacheco in 1610, after leaving the workshop of his first teacher, the hot-headed Francisco de Herrera, who taught Velázquez little more than a predilection for long-bristled brushes and how to duck an angry fist.

Pacheco, on the other hand, opened Velázquez up to a whole new world of possibilities. What Pacheco may have lacked in talent, he more than made up for in theory. According to contemporary writer Palomino, "Pacheco's house was a gilded cage of art and an academy and a school for the greatest minds of Seville. "

Pacheco tried to create an Italian-like humanist court, uniting the brightest minds in Spanish arts and sciences. Pacheco also authored the essay Arte de la Pintura to argue for the inherent nobility of painting and the visual arts in general, an argument which would prove to be a decisive influence on the young Velázquez.

After five years of studying under Pacheco, Velázquez had so astounded the older artist with his fine painting and eager ambition that the older artist consented to giving his daughter's hand in marriage. Velázquez married Juana Pacheco in 1618, at the ripe old age of nineteen.

The couple would have two daughters together, both of whom would die before their parents: Ignacia de Silva Velázquez y Pacheco, who died in infancy, and Francisca de Silva Velázquez y Pacheco, who survived long enough to marry an artist, but died in 1658, two years before her parents.

The years of his marriage marked an important stage in Velázquez's career. Around 1618 and 1619, Velázquez painted some of his most important early masterpieces (such as Old Woman Cooking Eggs),which were revolutionary for their realism and simplicity.

Velázquez could never content himself with his successful career in Seville. He had his sights set on greater things, and so at the beginning of April, 1622, the young artist set off for Madrid in the hopes of charming his way into the court.

Velázquez failed in his initial attempt to win the heart of King Philip IV, but luckily for him, in December of the same year the king's favorite court painter, Rodrigo de Villandrando, passed away.

Thanks to some strings pulled by the king's right-hand man Olivares, in August 1623 Velázquez went back to Madrid to paint the royal portrait. Philip sat for the up-and-coming artist on the 16th of that month. He was so enamored with the result, he immediately named Velázquez his sole and unique portrait painter and ordered all previous royal portraits to be recalled.

Velázquez was welcomed to court with a contract of twenty ducats per month, lodging, medical attendance, and payment for each of his paintings. Thus began a beautiful friendship between the artist and king, although the rest of the court was less than pleased with the new arrangements. The established royal painters looked upon the seemingly unqualified newcomer with disdain and suspicion.

In order to help qualm rumblings that Velázquez was a mere painter of "heads and hands" and lacked real artistic capability, in 1627 Philip IV held a competition for the "best painter of Spain," requiring all contestants to execute a picture depicting the expulsion of the Moors. Naturally, Velázquez won the competition, earning him the honor of being appointed "gentleman usher," with a raise of twelve reis per day (the same salary as for the royal barber) and an extra ninety ducats per year as a clothing allowance.

In 1628, that titan of the Flemish Baroque Peter Paul Rubens descended on the Spanish court on a diplomatic mission. The visit would have portentous implications on Velázquez's development as an artist.

Contemporary records show that the two artists struck up a friendship, frequently sketching together and exchanging artistic ideas. Although Rubens' style itself didn't necessarily have much of an impact on Velázquez, Rubens proved to be an enormous influence in another significant way: in his suggestion that Velázquez make the pilgrimage to Italy obligatory for all artists.

This initial trip to Italy (1629-1631) proved to be a shocking eye opener for the young artist and was decisive in the development of Velázquez's style. The trip was also a landmark in that it was entirely sponsored by Philip IV, an unusual act for a patron of the arts.

As one art historian eloquently stated, "Velázquez had left Madrid as a gifted if somewhat provincial painter; almost overnight he had not merely absorbed the lessons of Italian painting, but found a way to transcend them. "

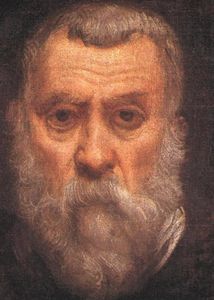

On this trip, Velázquez visited Genoa, Milan, Venice, Florence, Rome, and Naples, from whence he returned to Spain in January 1631. Along the way, he executed numerous sketches and copies and was most heavily influenced by the Venetian painters (especially Titian and Tintoretto), particularly in their depiction of space and use of light and color. By the time he returned to Spain, Velázquez had transcended to an entirely new level of painting.

Diego Velazquez Middle Years

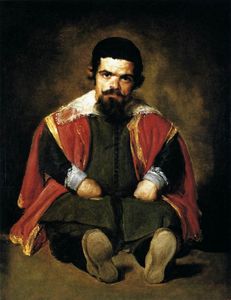

The 1630s were Velázquez's most fruitful years, artistically speaking. Although Velázquez's artistic output was far smaller than that of many other Baroque artists due to his manifold duties at court, the 1630s represent a veritable flood of inspiration, the very apogee of Velázquez's career.

In fact, an entire third of his entire oeuvre dates from this period, and furthermore Velázquez's paintings of the 1630s cover an unprecedented array of subjects.

On the other hand, the 1630s also represent an intensification of Velázquez's lust for glory, recognition and, most importantly, power. This desire for nobility and upward movement in the court would ultimately lead to a drop-off in Velázquez's artistic production.

This drop-off happened in the next decade. In the 1640s, Spain found itself in an increasingly worsening political and economic situation: in 1640, both Catalonia and Portugal rebeled, the war with France took a turn for the worse, Queen Isabella died in 1644, and the crown prince died in 1646.

Instead of stepping up to the task and attempting to steer his country out of this shambles, the rather pathetic Philip IV increasingly took comfort in retreating into his art collections. To this end, throughout this decade Velázquez was nominated to various new positions at the court, which involved responsibilities in decorating the apartment and maintaining the royal collection.

Unlike other Baroque artists of the court, like Bernini, Rubens, van Dyck, or Poussin, who focused mainly on the art and saw their courtly duties secondary, Velázquez's political position came to take supremacy over his art.

As part of his new position, in 1648 the king sent Velázquez on another trip to Italy in order to improve the royal collection, notably by acquiring new antiquities and sculpture, and bringing Italian fresco painters back to Madrid in order to revive this dying art in Spain.

This three-year-long expedition was no less inspiring than Velázquez's first trip south. This time, Velázquez was to paint one of the most famous paintings of his entire oeuvre, Portrait of Innocent X. This astonishingly bold, realistic portrait was executed at least in part as an attempt by Velázquez to be admitted into the most elite of Spain's noble orders: with the pope on his side, his chances were much improved.

Velázquez's second trip to Italy was quite successful: he managed to bring back an ample collection of antiquities and paintings for the Spanish King Philip IV, although he had a harder time with the fresco painters, who all feared the brutal working conditions in Spain. Velázquez's trip was successful in other fields, as well: the artist even found the time to father an illegitimate child, which was part of the reason his stay in Italy lasted three whole years, much to the King's chagrin.

Upon his return to Madrid, Velázquez was faced with even more responsibilities. The king remarried in 1649, meaning a whole slew of new portraits had to be executed, and then on 8 March 1652, Velázquez received his highest honor yet: he was nominated to the position of Aposentador Mayor de Palacio, thus effectively becoming the curator of the royal collection, the responsible for the royal quarters, and in charge of overseeing the king's travels. This promotion also spared Velázquez from the Inquisition, a real danger considering the artist's Jewish heritage.

By maintaining close ties to both the pope and king, Velázquez managed to accrue an unusual amount of power and influence at court, especially for a mere artist. Finally, by the 6 June 1658 (the year of his one surviving daughter's death), Velázquez finally got one step closer to his dream when he was nominated to the Order of Santiago. Amazingly, the artist was turned down two times by the order, necessitating two separate dispensations from the pope.

Being admitted into the Order of Santiago was the equivalent of being knighted and the order was particularly picky about its members. The two most important qualifications were that members were descended from demonstrable nobility on both sides of the family, and that no member of the family had engaged in "manual" labor (including painting).

Velázquez obviously met neither of those requirements, but the fact that the Order finally gave in (admittedly, under heavy pressure from both the king and pope) was a major step in recognizing the arts as elevated above artisanal labor.

Diego Velazquez Advanced Years

In 1660, the devastating war between France and Spain finally ended and the countries were united with the marriage of the infant Maria Theresa and the King of France, Louis XIV.

As part of his official duties, Velázquez travelled to the French-Spanish border to the Island of Pheasants in order to execute the decoration and "scenic display."

The work was exhausting and the climate unforgiving. Velázquez returned to Madrid on June 26, only to be struck with a fatal fever on July 31. Velázquez died on the 6th of August, to be followed by the death of his wife only four days later.

Velázquez was buried in the Church of San Juan Bautista, which was demolished by the French in 1811. To this day, the whereabouts of Velázquez's remains is unknown.