Las Meninas

- Date of Creation:

- circa 1656

- Alternative Names:

- The Family of Felipe IV

- Height (cm):

- 318.00

- Length (cm):

- 276.00

- Medium:

- Oil

- Support:

- Canvas

- Subject:

- Scenery

- Art Movement:

- Baroque

- Created by:

- Current Location:

- Madrid, Spain

- Displayed at:

- Museo Nacional del Prado

- Owner:

- Museo Nacional del Prado

- Las Meninas Page's Content

- Story / Theme

- Analysis

- Critical Reception

- Related Paintings

- Artist

- Art Period

- Bibliography

Las Meninas Story / Theme

Voted as the best painting in the history of art in 1985, Velázquez's Las Meninas is almost impossible to define. At the most basic level, the painting is a group portrait of the five-year-old Infanta Margarita, her ladies-in-waiting and other members of the court, the King and Queen of Spain, and Velázquez himself.

At the same time, it is also a painting about art, illusion, reality, and the creative act itself, as well as a claim for the nobility of artists and the fine arts in general.

Las Meninas is set in the Grand Room (the Pieza Principal) of the deceased crown prince Baltasar Carlos's living in quarters. King Philip IV gave the room to Velázquez in the 1650s to use as his personal studio, a very high honor indeed.

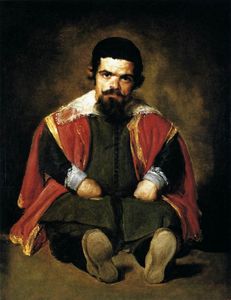

The participants in this piece include: In the center: the Infanta Margarita (1), flanked to the right by lady in waiting Dona Isabel de Velasco (2), and on the left María Agustina Sarmiento de Sotomayor (3). To the right of the picture plane are the two dwarves: the German woman Maribarbola (4), and the Italian man Nicolas Pertusato (5), who is caught in the act of kicking the poor, aggravated royal hound. Behind this group are the royal chaperone, dona Marcela de Olloa (6), and an anonymous bodyguard (7). In the deepest level of the painting, framed in the brightly lit doorway is the Queen's Chamberlain and head of the royal tapestry works, Don José Nieto Velázquez (8), a possible relative of the artist. Finally, the King and Queen (10, 11) are present in their reflection in the mirror on the rear wall of the room. Velázquez (9) himself appears to the far left of the composition, painting an enormous canvas with its back turned towards the viewer.

The Commission:

Las Meninas was yet another commission from the King. By the time Velázquez set to work on this, the apogee of his oeuvre, he had been the official court painter for thirty-three years.

The great bulk of his work at court consisted of painting royal portraits (he painted at least forty portraits of Philip IV alone), and this picture was essentially commissioned as more of the same: a group portrait of the royal family and their attendants. On so many levels, however, the painting is much, much more.

Las Meninas Analysis

The Composition:

If Las Meninas was voted as the greatest painting of all time, it is largely due to the extraordinary and innovative complexity of the composition. Velázquez's painting may appear relatively simple and straightforward at first glance, but a closer inspection reveals that Las Meninas is a composition of striking intricacy.

• Layers of depth:

the picture plan of Las Meninas is divided into a grid system, of quarters horizontally, and sevenths vertically. Furthermore, the canvas is divided into seven layers of depth, as well. Las Meninas has the deepest, most carefully defined space of any Velázquez painting, and is the only painting where the ceiling of the room is visible.

• Patterns and connections:

For such a large, multi-figure composition, excellent organization is of the essence. Velázquez managed to instill order in Las Meninas by utilizing a system of curved and diagonal lines. He ordered the figures in the foreground along an X shape with the infant Margarita in the center, thus emphasizing her importance and making the five-year-old child the focal point of the composition.

Velázquez masterfully uses light and dark to further order the composition. With light and shadow, he creates a system of double arcs that further centralizes the Infanta, one above that starts with Velázquez, descends to the Infanta, and rises to Nieto in the background, and one below, created by the arc of light in the foreground.

• Frames:

Velázquez's Las Meninas is a picture about frames and framing. All the figures are framed by the very room in which they are situated, while literal frames exist in the form of the canvas on the left, the frames of the paintings on the rear wall, the doorway that frames Nieto, and finally the mirror that frames the royal couple.

Style:

Stylistically, Las Meninas is like the sum of the best parts of all of Velázquez's earlier paintings. Just like his early bodegones, the paintings is marked for its intense, Caravaggesque chiaroscuro, a limited and somber palette, a photo-like realism, and remarkably loose, free, unrestrained brushstrokes.

Las Meninas Critical Reception

Velázquez's Las Meninas is perhaps the painting most open to interpretation in the entire history of art. The following are the most prominent and most plausible interpretations, put forth by the most erudite of art historians.

One of the earliest and most widely accepted interpretations of Las Meninas is that the painting is Velázquez's personal manifestation of the inherent nobility of painting. The painting was executed during the years of Velázquez's attempts to gain admission into the elitist Order of Santiago, who turned the artist down twice (despite the support of the King and the pope) because of his artist status.

In 17th century Spain, artists were grouped in the same social level as blacksmiths or tailors, because they were paid for labor they did with their hands. Velázquez fought for most of his career to elevate the status of the arts in Spain to the same level of respect and admiration as in Italy.

Numerous clues in the painting support this interpretation, for example, Velázquez is shown in the private quarters of the deceased crown prince, in the company of the King, Queen, and the last remaining heir, and only the very closest members of the court: he is, in essence, a part of the family.

Recently, a new interpretation has been put forth, suggesting that the painting might have been commissioned in light of some very particular circumstances. At the time that Las Meninas was painted, the crown prince Baldasare Castiglione had passed away in a riding accident and the Infanta Margarita was the King's only surviving child.

There has been speculation that before the birth of Carlos II, the monarchy was considering grooming the Infanta to eventually rule the country, like Queen Christina of Sweden.

In a more general sense, many art historians have proposed (undoubtedly with reason) that Las Meninas is essentially about the relationship between reality and illusion, life and art, a consuming preoccupation during the Spanish Baroque.

Las Meninas Related Paintings

Las Meninas Artist

When Velázquez first entered court, the established painters scoffed at the unproven young talent, calling him only good for mediocre portraits and lacking the scope for subjects of greater weight. Velázquez proved the naysayers wrong, works like Las Meninas, which is among the most exquisite in the history of art.

Velázquez has not ceased to be a remarkably fecund source of inspiration for art critics and art historians up until the present day, nor has his reputation as one of the greatest painters of all time been dimmed.

Velázquez paved the way for early nineteenth century realist and impressionist painters, especially Édouard Manet. Since then, he has gone on to influence artists as diverse as Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, and Anglo-Irish painter Francis Bacon. Such artists have demonstrated their love for the works of Velázquez by recreating some of his most noted paintings.

Diego Velázquez was hailed a father of the Spanish school of art and is one of the greatest artists that ever lived.

Las Meninas Art Period

Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez was born into a society of paradox: Spain was simultaneously undergoing one of the most dramatic economic and political declines of any nation in European history, and unprecedentedly fertile, creative bursts of artistic activity.

In Velázquez's hometown of Seville in particular, circles of Humanist learning, arts and letters and philosophy all flourished, constituting a particularly fecund environment for a young artist.

On the other hand, Velázquez's chosen profession would become a significant obstacle in the artist's personal agenda. Spanish society was obsessed with nobility, and unlike in Italy, the visual arts were emphatically not equated with noble pursuits like literature or philosophy. Artists were seen as essentially vulgar craftsman who worked for a living with their hands, just like blacksmiths or tailors.

Making matters even more complicated, the Catholic church exercised almost total power over the arts in Spain, dictating everything from subject to composition, meaning that artists had very little room to experiment or grow. Velázquez was thus fated to struggle from the very incipience of his career.

While most artists of the Baroque period suffered from a serious drop in critical opinion during the 18th century, eventually fading into oblivion until being rediscovered in the 1950s, Velázquez took an alternate route.

Because of Spain's political situation, the nation was more or less isolated from the rest of Europe during the heights of Neoclassicism, meaning that Velázquez's reputation was safe from the hands of Baroque-haters like Wincklemann, who managed to destroy the reputation of such artists as Caravaggio, Carracci and Bernini.

By the time Spain opened up to the rest of Europe in the beginning of the 19th century, the world was ready for Velázquez, and critics and artists alike haven't ceased singing the master painter's praises.

Las Meninas Bibliography

The following list offers some of the best sources of further reading on Velázquez and his works.

• Brown, Dale. The World of Velázquez: 1599-1660. Time-Life Books, 1969

• Brown, Jonathan. Velázquez, Painter and Courtier. Yale University Press, 1986

• Carr, Dawson, et al. Velázquez. Yale University Press, 2006

• Davies, David, et al. Velázquez in Seville. National Galleries of Scotland, 1996

• Harris, Enriqueta. Velázquez. Phaidon, 1982

• Kahr, Madlyn Millner. Velázquez: the art of painting. Harper and Row, 1976

• López-Rey, José. Velázquez: A catalogue raisonné of his œuvre Faber and Faber, 1963.

• Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso, et al. Velázquez. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989

• Wolf, Norbert. Diego Velázquez, 1599-1660: the face of Spain. Taschen, 1998

• Wind, Barry. Velázquez's Bodegones: A study in 17th century Spanish genre painting. Fairfax: George Mason University Press, 1987