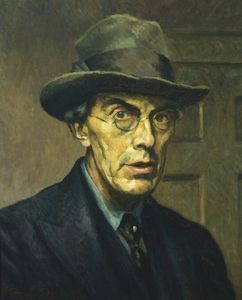

El Greco

- Full Name:

- Doménikos Theotokópoulos

- Date of Birth:

- 1541

- Date of Death:

- 07 Apr 1614

- Focus:

- Paintings, Sculpture

- Mediums:

- Oil, Tempera, Wood

- Subjects:

- Figure, Scenery

- Art Movement:

- Mannerism

- Hometown:

- Unknown City of Crete, Italy

Introduction

El Greco was born in Crete, during the time it was part of the Republic of Venice and a hub of Post-Byzantine art. He became a master in this art form before following in the footsteps of other Greek artists and travelling to Venice to further his studies.

Moving on to Rome, El Greco opened a workshop and spent a great deal of time developing his style, adopting elements of both Mannerism and the Venetian Renaissance.

However, it was after relocating to Toledo, Spain that El Greco truly blossomed. There he received several major commissions and produced his best known paintings.

The artist gained notoriety for his highly expressive and visionary religious works and rarely ventured away from this genre. When he did, however, he created compelling portraits, landscape paintings, mythological works and sculptures.

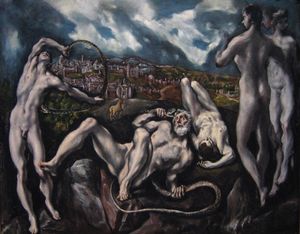

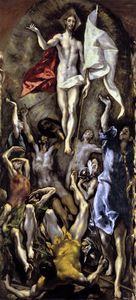

Those produced during his later years are particularly notable for their undulating forms, epic scale and expressive distortions.

El Greco regarded color as the most important element of painting, and declared that it had primacy over form. In his mature works he tended to dramatize rather than describe and the strong spiritual emotion of his works directly affects the audience.

El Greco Artistic Context

Mannerism was a period of European art history that followed close on the heels of the Renaissance and was sometimes referred to as the Late Renaissance. While some critics consider Mannerism as part of the Late Renaissance, others classify this as a distinct period occurring between 1520 and 1600, when naturalism gave way to the surreal.

Although El Greco was technically considered a Mannerist, this early work is very reminiscent of Byzantine art, by which El Greco was heavily influenced.

El Greco's works were worlds apart from his contemporaries due to their dramatic and expressionistic style and it was not until the 18th century that his unique approach was appreciated.

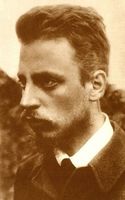

The artist is seen as a forerunner of both Expressionism and Cubism and he also inspired writers and poets including Rainer Maria Rilke and Nikos Kazantzakis.

Fusing Byzantine traditions with Western art, El Greco is noted for his extended figures and often fanciful pigmentation and because of this many modern scholars believe that El Greco is a truly unique artist who broke the rules of all conventional schools.

Many regard El Greco as one of the finest painters of Spain, if not all of Western Art.

El Greco Biography

Early years:

El Greco was born in 1541, in either the village of Fodele or Candia (now known as Heraklion) in Crete to a prosperous family. His initial training took place at the Cretan school but as Crete was owned by the Republic of Venice during this time, it made sense for El Greco to take up his career in Venice. It's thought he went there around 1567, although there is little information about the artist's time in the city.

In 1570, El Greco moved to Rome and produced a series of works reflecting his studies in Venice. Thanks to the artist Giulio Clovio, El Greco was invited to the Palazzo Farnese, which was a vibrant art centre set up by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese.

There El Greco met the acquaintance of many elite citizens, including the Roman scholar Fulvio Orsini, who went on to collect many of his paintings.

El Greco set himself apart from other Cretan artists by evolving his style and inventing new and rare interpretations of traditional religious themes. His works from this period exemplified the Venetian Renaissance style with elongated figures, chromatic framework and sometimes multi-figured compositions in vibrant landscapes, drawing inspiration from artists such as Titian and Tintoretto.

In Rome many aspiring artists were influenced by the works of Michelangelo and Raphael but El Greco was eager to introduce his own artistic views, ideas and techniques.

Middle years:

In 1577 El Greco relocated to Toledo, although he had no plans to settle there permanently. His main aim was to catch the attention of King Philip and to gain royal commissions.

He succeeded and was appointed to paint two works, but the King was seemingly unhappy with both, for reasons unknown, and did not employ the artist again.

Advanced years:

Despite this setback El Greco was obliged to remain in Toledo and was hailed a great painter. In 1586 he was commissioned to paint The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, now regarded as his masterpiece.

The artist was extremely prolific between 1597 and 1607, receiving several major commissions. Furthermore, the workshop he opened produced illustrative and sculptural pieces for various religious institutions.

It's believed that from 1585 onwards El Greco lived in a plush complex belonging to the Marquis de Villena, where he also housed his workshop. He spent his last years living comfortably and continued to study.

It's possible that the artist lived with his Spanish female companion, Jerónima de Las Cuevas, although this has not been confirmed. The couple did, however, have a son together (the artist's only child) named Jorge Manuel who followed in his father's footsteps and became a painter.

While working on a commission for the Hospital Tavera El Greco fell seriously ill and passed away on April 7, 1614.

El Greco Style and Technique

El Greco:

"I hold the imitation of color to be the greatest difficulty of art."

-

-

El Greco:

"I would not be happy to see a beautiful, well-proportioned woman, no matter from which point of view, however extravagant, not only lose her beauty in order to, I would say, increase in size according to the law of vision, but no longer appear beautiful, and, in fact, become monstrous."

Religious works:

Although El Greco was technically considered a Mannerist, many of his early works are very reminiscent of Byzantine art, by which he was heavily influenced.

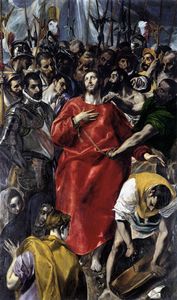

In works such as The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, the artist's elongated figures, dissonant use of light, brilliant colors, artificiality and lack of depth are typical elements of the Mannerist style.

Furthermore, in The Purification of the Temple, the artist elongates and twists bodies almost to the point of parody, and his bold brushwork and dramatic lighting give the painting a Mannerist feel.

El Greco was also heavily influenced by the fine churchmen and influential members of Toledan society and God when creating his religious paintings.

Portraiture:

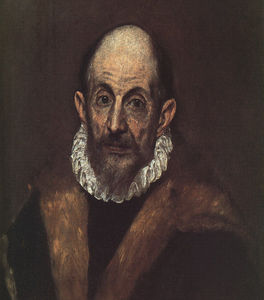

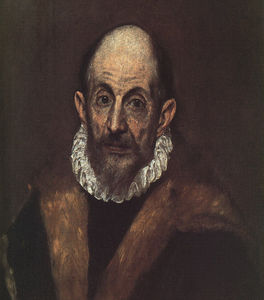

El Greco created a small number of portraits during his time and was skilled in capturing not only his sitter's features but also their character. Such works are of the same quality as his religious paintings.

Harold Wethey says that "by such simple means, the artist created a memorable characterization that places him in the highest rank as a portraitist, along with Titian and Rembrandt".

Architecture and sculpture:

As well as painting, El Greco was also a skilled architect and sculptor and often carried out a variety of artwork for particular buildings. His produced several altar compositions too.

At the Hospital de la Caridad El Greco produced a variety of sculptures and paintings but it's likely that his wooden altar and sculptures have since perished.

Toledo:

Many scholars believe that El Greco's time in Toledo was central to the development of his mature style and showcased his ability to adapt it according to his surroundings.

Harold Wethey asserts that "although Greek by descent and Italian by artistic preparation, the artist became so immersed in the religious environment of Spain that he became the most vital visual representative of Spanish mysticism".

El Greco Works

El Greco Followers

It was not until after his death that El Greco's work was truly appreciated. Since the 18th century it has been valued by scholars and artists alike and has proved a great source of inspiration for many modern painters.

Eugène Delacroix and Édouard Manet:

El Greco's expressiveness and colors were particularly inspirational to Delacroix and Manet. According to Efi Foundoulaki, "painters and theoreticians from the beginning of the 20th century 'discovered' a new El Greco but in process they also discovered and revealed their own selves".

Paul Cezanne:

One of the pioneers of Cubism, Cezanne adopted similar elements to El Greco, such as the use of space and distortion of bodies.

Fry noted that Cézanne drew from "his great discovery of the permeation of every part of the design with a uniform and continuous plastic theme".

Pablo Picasso:

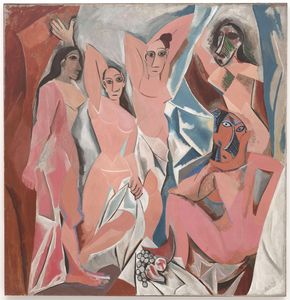

During his 'Blue Period', Picasso admired the connection of colors in El Greco's work, and it was highly influential when he created Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.

Picasso's early cubist discoveries unlocked other aspects of El Greco's work: the link between form and space, analysis of the arrangement of his compositions and his use of highlights.

Several key Cubist features relating to distortions and timing, are reminiscent of El Greco's creations and Picasso believed El Greco's structure to be Cubist.

Jackson Pollock:

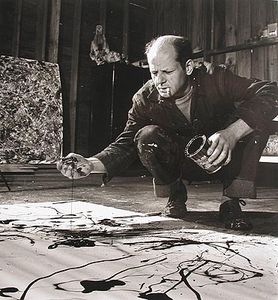

Expressionism was inspired by El Greco's expressive distortions and Pollock, a key player in the abstract Expressionism, produced sixty drawing compositions after El Greco.

Literary greats:

El Greco's work Immaculate Conception was the inspiration for Rainer Maria Rilke's poem Himmelfahrt Mariae I. II. , 1913. Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis, wrote a tribute to El Greco in his autobiography which he named Report to Greco.

El Greco Critical Reception

Posthumous reception:

After his death, El Greco's work continued to be met with disdain due to the fact that it was so far removed from the principles of the early Baroque style that emerged near the beginning of the 17th century and soon replaced 16th-century Mannerism for good.

El Greco's work was confusing for art fans and artists of the time, and therefore he had no real followers. Late 17th and early 18th-century Spanish critics admired his talent but not his complex iconography and anti-naturalistic style.

18th Century reception:

El Greco's works were re-assessed in the late 18th century and French author Théophile Gautier, believed him to be a pioneer of the European Romantic movement.

In 1908, Julius Meier-Graefe, an academic of French Impressionism, travelled in Spain and later produced a book - Spanish Journey - naming El Greco as a great painter of the past and a prophesy modernity;

"He [El Greco] has discovered a realm of new possibilities. Not even he, himself, was able to exhaust them. All the generations that follow after him live in his realm. There is a greater difference between him and Titian, his master, than between him and Renoir or Cézanne. Nevertheless, Renoir and Cézanne are masters of impeccable originality because it is not possible to avail yourself of El Greco's language, if in using it, it is not invented again and again, by the user."

English artist and critic Roger Fry agreed with Meier-Graefe, describing El Greco as "an old master who is not merely modern, but actually appears a good many steps ahead of us, turning back to show us the way".

El Greco Bibliography

To read more about El Greco please choose from the following recommended sources.

• Alcolea, Santiago. El Greco. Ediciones Poligrafa, 2007

• Bray, Xavier. El Greco (National Gallery of London). Yale University Press, 2004

• Carr, Dawson W. El Greco to Goya: Spanish Painting (National Gallery Company). Yale University Press, 2009

• Davies, David. El Greco (National Gallery Company). Yale University Press, 2005

• Kazantzakis, Nikos. Report to Greco. Faber and Faber, 2001

• Scholz-Hansel, Michael. El Greco: Domenikos Theotokopoulos 1541 - 1614 (Taschen Basic Art Series). Taschen GmbH, 2004