Laocoon

- Date of Creation:

- circa 1614

- Height (cm):

- 137.50

- Length (cm):

- 172.50

- Medium:

- Oil

- Support:

- Canvas

- Subject:

- Figure

- Framed:

- Yes

- Art Movement:

- Mannerism

- Created by:

- Current Location:

- Washington, District of Columbia

- Displayed at:

- National Gallery of Art Washington

- Owner:

- National Gallery of Art Washington

Laocoon Story / Theme

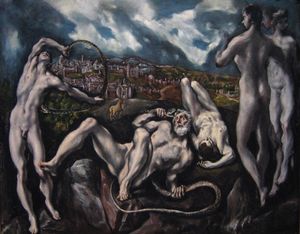

Produced late in El Greco's career, the enigmatic and moving Laocoon is his only masterpiece with a mythological subject, taken from Virgil Aeneid. While mythology was dear to Renaissance Greats, it was an anomalous theme for El Greco.

Virgil's Latin epic poem, Aeneid, written in the first century BCE, tells the tragic tale of Laocoon, a Trojan priest who tries to warn Troy about the dangers of a Wooden Horse gifted at their gates by the scheming Greeks.

Alas, his warning is not heeded and Troy admits into their city the horse, which is filled with Greek soldiers who proceed to bag the city, thus marking the beginning of the end for Troy.

To add insult to injury, Laocoon is punished by Minerva who, in siding with the Greeks, sends serpents to slaughter him and his two sons.

In his stirring piece, El Greco shows this serpentine attack, though he has made a few important modifications to suit his purpose in painting this scene. Moreover, he adds a twist to his own rendition, however, by replacing Troy with Toledo in his painting.

After El Greco's death, among his possessions were one large version of this work and two smaller ones, though today only one painting remains.

Laocoon's plea to Troy, Aeneid, written by Virgil in the first century BCE:

"'O my poor people,

Men of Troy, what madness has come over you?

Can you believe the enemy truly gone?

A gift from the Danaans, and no ruse?

Is that Ulysses' way, as you have known him?

Achaeans must be hiding in this timber,

Or it was built to butt against our walls,

Peer over them into our houses, pelt

The city from the sky. Some crookedness

Is in this thing. Have no faith in the horse!

Whatever it is, even when Greeks bring gifts

I fear them, gifts and all. '"

Laocoon Inspirations for the Work

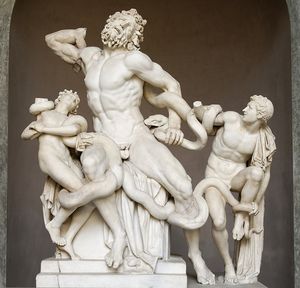

One of many prevailing theories about Laocoon is that El Greco chose this particular mythological theme because of an earlier sculpture capturing this tale.

The mythological story of Laocoon was dramatically depicted in a first-century Roman sculpture attributed to three sculptors: Hagesandros, Polydoros and Athenodoros of Rhodes (see Related works below).

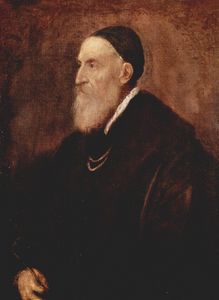

The discovery of this ancient piece made a big impression on the Renaissance artists including Michelangelo and Titian, two of El Greco's mentors. Many painters at this time claimed that this statue was one of the greatest ever made.

Some people believe that El Greco's inspiration stemmed from a desire to outdo this beloved classic so adored by the cohort of craftsmen that came before him.

Toledan Comuneros:

Art historian Marek Rostworowski argues that El Greco was inspired to make this Toledan rendition of the Laocoon as a tribute to those who died in the tragedy of the Castilian War of the Communities and the revolt of Toledo's comuneros in 1520-1521.

Under this theory, it is possible that the citizens of Toledo commissioned El Greco to commemorate their tragedy under the guise of a mythological tale, so as not to anger the current ruler and grandson of Charles.

Laocoon Analysis

Composition:

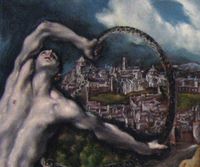

In El Greco's Laocoon, the city in the background isn't Troy; it is Toledo, the Spanish town where El Greco spent a majority of his adult life and a home for which he felt fervent affinities.

Here, El Greco's Toledo shows the fortified town with the mythological horse standing before its main gate. Additionally, it shows Toledo's Puerta Nueva de Bisagra, built in the mid-1500s by Charles, decorated with a two-headed eagle, a symbol of imperial rule defiantly rejected by Toledans.

In the foreground of El Greco's Laocoon are two figures (and an additional unfinished figure, to complicate matters), which seem suspended in mid air.

The man of the finished pair is looking towards the city, while the female is looking sharply in the opposite direction. The third, unfinished figure, appears to gaze towards Toledo.

Center stage, we find the anguished Laocoon fighting off Minerva's snake in vain, along with his two sons, also on the losing end of the serpentine struggle.

Color palette:

El Greco's palette of grays for the bodies and landscape is juxtaposed with the verdant backdrop of a Toledan Troy. Furthermore, the tension and anguished mood set by the figures in the foreground are heightened by the contrasting colors of the looming sky.

Contorted Pale Figures:

All of the figures in this painting are naked, as befits mythological characters.

Each of the men looks as if they caught some paling plague, their sickly colored muscular figures contorted and elongated in the typical Mannerist fashion.

Use of light:

As with most of El Greco's works, Laocoon displays harsh unnatural lighting that makes the scene surreal.

Laocoon Critical Reception

While some critics believe that El Greco painted the Laocoon as tribute to Toledan freedom fighters of the 1500s, others feel that his choice of this mythological theme, which was the subject of a classic Roman sculpture from the first century BCE, is evidence of his wish to prove he could rival the artistic works of the ancients.

The Toledan tribute theory:

Art historian Marek Rostworowski argues that the explanation of El Greco's Laocoon lies in the history of Toledo. In his view, Laocoon is a tribute to Toledo's stormy history. Herein, the mythological tale is used to express the tragedy of the Castilian War of the Communities and the revolt of Toledo's comuneros in 1520-1521.

Rostworowski suggests that El Greco painted the Laocoon in honor of the late Toledo heroes of the comunero uprising. It is possible, he claims, that the citizens of Toledo commissioned El Greco to commemorate their tragedy under the guise of a mythological tale, so as not to anger the current ruler and grandson of Charles.

In this interpretation, the male onlooker is Juan de Padilla, and the woman his wife Maria Pacheco, portrayed as facing sharply away from the city she was forced to flee.

The tragic threesome of Laocoon and his sons may serve to represent the ill-fated communeros. The Trojan horse may symbolize the dubious treaty that opened up the Toledo to their own besiegers.

Laocoon Related Paintings

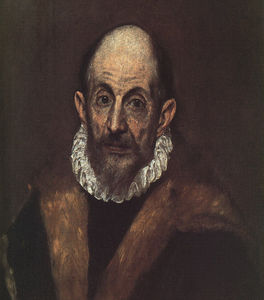

Laocoon Artist

El Greco completed the Laocoon late in his career at the age of 69. While he painted this scene more than once, it is the only mythological theme he chose during his career, which was focused primarily on religious images. Thus, critics believe that El Greco had particular motives in painting this work that had little to do with mythology.

El Greco was born in Crete, during the time it was part of the Republic of Venice and a hub of Post-Byzantine art. He became a master in this art form before following in the footsteps of other Greek artists and travelling to Venice to further his studies.

Moving on to Rome, El Greco opened a workshop and spent a great deal of time developing his style, adopting elements of both Mannerism and the Venetian Renaissance.

However, it was after relocating to Toledo, Spain that El Greco truly blossomed. There he received several major commissions and produced his best known paintings.

The artist gained notoriety for his highly expressive and visionary religious works and rarely ventured away from this genre. When he did, however, he created compelling portraits, landscape paintings, mythological works and sculptures, and those produced during his later years are particularly notable for their undulating forms, epic scale and expressive distortions.

El Greco regarded color as the most important element of painting, and declared that color had primacy over form. In his mature works he tended to dramatize rather than describe and the strong spiritual emotion of his works directly affects the audience.

Laocoon Art Period

El Greco completed the Laocoon towards the end of the Mannerist period, which was exemplified by elongated and twisted figures, artificiality, the supernatural and the bizarre. Mannerism followed on the heels of, and was in some ways a reaction against, the Renaissance and its penchant for classicism and naturalism.

El Greco's works were worlds apart from his contemporaries due to their dramatic and expressionistic style and it was not until the 18th century that his unique approach was appreciated.

The artist is seen as a forerunner of both Expressionism and Cubism and he also inspired writers and poets including Rainer Maria Rilke and Nikos Kazantzakis.

Marrying Byzantine traditions with Western painting, El Greco is renowned his elongated figures and often fantastic pigmentation and because of this many modern scholars believe that El Greco is a truly unique artists who broke the rules of all conventional schools.

Many regard El Greco as one of the finest painters of Spain, if not all of Western Art.

Laocoon Bibliography

To read more about El Greco please choose from the following recommended sources.

• Alcolea, Santiago. El Greco. Ediciones Poligrafa, 2007

• Bray, Xavier. El Greco (National Gallery of London). Yale University Press, 2004

• Carr, Dawson W. El Greco to Goya: Spanish Painting (National Gallery Company). Yale University Press, 2009

• Davies, David. El Greco (National Gallery Company). Yale University Press, 2005

• Kazantzakis, Nikos. Report to Greco. Faber and Faber, 2001

• Scholz-Hansel, Michael. El Greco: Domenikos Theotokopoulos 1541 - 1614 (Taschen Basic Art Series). Taschen GmbH, 2004