Raphael Critical Reception

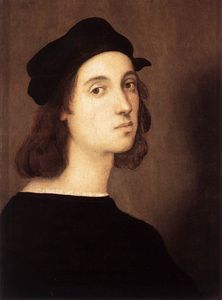

- Full Name:

- Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino

- Short Name:

- Raphael

- Alternative Names:

- Raphael, Raffaello Santi, Raffaello Sanzio

- Date of Birth:

- 06 Apr 1483

- Date of Death:

- 06 Apr 1520

- Focus:

- Paintings, Architecture, Drawings

- Mediums:

- Oil, Stone, Glass

- Subjects:

- Figure

- Art Movement:

- Renaissance

- Hometown:

- Urbino, Italy

- Raphael Critical Reception Page's Content

- Introduction

- During Life

- After Death

Introduction

Many of Raphael's compositions attracted wide currency in Europe during his lifetime due to engravings by Marcantonio Raimondi, who worked exclusively for Raphael between about 1510 and the artist's death in 1520.

Marcantonio reproduced finished works by Raphael and also made prints after designs that were expressly produced to be engraved. This helped ensure Raphael's fame during his lifetime, and continued widespread appeal after his death.

Raphael During Life

Raphael was one, if not the most celebrated artist of the High Renaissance. Whilst regarded as a superb talent from an early age, it was after arriving in Rome (and conquering it artistically) that he achieved fame as "the prince of the painters" of the brilliant papal court. By the time the last frescoes of the Stanza d'Eliodoro were complete in 1514, Raphael had become a household name in Rome.

Further suggestion of the esteem he enjoyed is shown by Leo X's chief minister, papal treasurer Cardinal Bernardo Bibbiena, offering his niece as a wife. This not insignificant gesture was rejected by Raphael on the grounds that the Pope would perhaps make him a cardinal, demonstrating again the high regard the papacy held for him.

Raphael's authority on art was viewed as such that by the end of his life he was effectively in charge of the Vatican's artistic work in Rome, encompassing paintings, architecture and archeology.

Raphael After Death

Raphael's greatness is most easily measured by the range of art he influenced or inspired. In the first half of the 16th century many of his pictorial ideas were widely disseminated in somewhat coarsened form by his pupil Giulio Romano. These pictorial ideas also developed into new ornamental directions by some of his younger workshop assistants.

His art provided a crucial ingredient in the elegant aesthetic of Parmigianino (who was at times described as 'Raphael's reincarnation'). Raphael is therefore one of the progenitors of Mannerism.

Furthermore study of two or three of his inventions determined the astonishing innovations of Correggio, especially in the painting of domes, which were adopted by Baroque artists in the following century. The finest of Titian's early portraits, which were repeatedly imitated for several centuries, seem to depend upon knowledge of Raphael's portrait of Castiglione.

Raphael's methods of preparing to paint, such as his practice of drawing from the nude model, of adjusting his ideas by reference to nature and of studying drapery and extremities separately, were largely abandoned after his death by his pupils and not followed widely by many leading 16th century artists.

At the end of the century, however, these methods became exemplary in the artistic teaching established by the Carracci family in Bologna. They were thus incorporated into the discipline of the art academies that spread over Europe in the following centuries. The ideal of heroic narrative painting, or even the very idea of history painting, which such academies propounded was exemplified by the rhetoric of Raphael's The Transfiguration and his tapestry cartoons. The most authoritative writers on art in the 17th and 18th centuries revered Raphael's work almost without qualification.

The impact of Raphael's greatest inventions has been dulled somewhat by the association with academic art. Although he was the hero of Rubens as well as Nicolas Poussin, and later of Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, the normative status that these artists gave to his work has certainly done much to diminish his popularity.

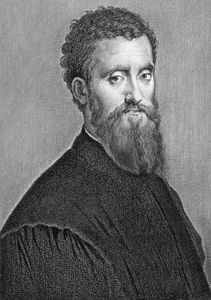

Furthermore, what is actually known of his life has not always helped his 'artistic' reputation. Raphael's genial and obliging character, his efficient assimilation of the innovations of others and his remarkable managerial skills do not often match up with modern notions of 'artistic genius'. Such notions are better exemplified by Leonardo and Michelangelo, with whom Raphael is inevitably compared.