Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo

- Date of Creation:

- 1759

- Height (cm):

- 100.40

- Length (cm):

- 126.50

- Medium:

- Oil

- Support:

- Canvas

- Subject:

- Figure

- Art Movement:

- Rococo

- Created by:

- Current Location:

- London, United Kingdom

- Displayed at:

- Tate Britain

- Owner:

- Tate Britain

- Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo Page's Content

- Story / Theme

- Inspirations for the Work

- Analysis

- Critical Reception

- Related Paintings

- Locations Through Time - Notable Sales

- Artist

- Art Period

- Bibliography

Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo Story / Theme

Hogarth based Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo on a scene from 'The Decameron', a collection of 100 stories written by the Italian Giovanni Boccaccio in the 14th century.

This literary work is structured in what's known as a 'frame narrative' and tells the tale of a group of seven women and three men who escape from the Black Death in Florence. They spend 14 days together in a villa outside of the city and to pass the time take it in turns to tell personal stories, all of which are set around certain themes.

The story of Sigismunda was told on the 4th day of The Decameron and is centered on a princess and her new husband Guiscardo;

• Sigismunda is the daughter of a Prince Tancred of Salerno

• She marries the man she loves in secret. His name is Guiscardo and he is a commoner with no social standing

• When her father finds out he orders his guards to kill the man and present his heart to Sigismunda in a golden cup

• Distraught at the death of her love Sigismunda then adds poison to the cup and drinks from it, killing herself

Hogarth has depicted Sigismunda clutching the cup to her heart, distraught at the loss of her husband, by her own father's hand.

This painting was commissioned by Sir Richard Grosvenor who gave the artist the choice of painting whatever subject matter he wished. Hogarth decided to have another try at producing a biblical or historical painting which he had previously been criticized for.

Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo Inspirations for the Work

It's believed that Hogarth modeled Sigismunda on his wife Jane. The artist also drew inspiration from the following sources;

Theatre:

Hogarth, in his autobiographical notes, says that he was familiar with the story of Sigismunda and had an interest in painting the subject sometime before creating this piece. However it would be unwise to discount the influence of a theatrical adaptation of the subject by James Thomson in 1745.

After all, the theatre is known to have been a big influence on Hogarth throughout his career so it stands to reason that it may well have been for this painting too.

The Old Masters:

Although Hogarth expressed his distaste for the old Renaissance masters, as his health declined with age it is thought that his somewhat pompous attitude got the better of him. It forced him to mirror their style and themes to prove himself as an artist.

To produce Sigismunda Hogarth used some very recognizable Renaissance techniques, including;

A dark background with various plays on light and shadow

Placing a self-portrait, seen in the carved face of the table, within the painting as a way of signing the work

The subject matter was thought to be derived from Correggio's work on the same subject, but Hogarth later wrote that the work was mainly influenced by Francesco Furini. Hogarth certainly priced this painting at the same level as Correggio's original Sigismunda, which had recently been sold in London.

Literature:

The main inspiration behind this work is Giovanni Boccaccio's The Decameron which was originally written in Italian and would not have been available until it was translated into English in John Dryden's 'Fables, Ancient and Modern' in 1699. However, the stories themselves may have been spread through Europe orally prior to this date.

Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo Analysis

In Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo Hogarth takes inspiration from the Renaissance masters and uses color, brushwork and composition to create drama and sorrow in the painting.

Composition:

The compositional aspect of this work relates a lot to Hogarth's ideas in his Analysis of Beauty. The use of yellow as a primary color within the piece accentuates the cup as well as creating a strong paradox on the brilliant aquamarine blue of the dress.

Numerous serpentine curves and lines also help the eye move easily across the work and can be seen in her hand, the numerous folds and creases in her dress and the rich ornamentation of the furniture.

Color palette:

Hogarth's palette here is very rich and the palette is bold, bright and rich in its texture. The most striking color is the blue of Sigismunda's dress which creates a focus in the gloomy scene and is juxtaposed by the rich purple skirt to the bottom.

Hogarth's use of yellows is also rich and unlike some of his other works it is not muted and this creates a narrative in the painting.

Sigismunda's flesh tones are created using pure white mixed with bright oranges and stark red undertones where the light falls on her face. On her right the artist uses the same blue tones within the dress to create a sense of shadow as it faces away from the incoming light.

He uses the same red carmine for the fresh heart in the cup as well.

Warm light browns are used for her hair and the carved leg tables, while grays are used for the top and the background walls.

Brush work:

The painting is very much fashioned in the Rococo style. Hogarth uses numerous long, loose, natural free flowing lines with fine attention to detail for the curved and ornate decoration in the dress, surfaces and objects.

The artist uses Serpentine line frequently in the work and focuses on the aesthetic visual stimulation that Rococo offered to its audiences.

There is fine dabbling for the marbled table top and for the fine intricate detail in the cup.

The layering on the marble table is not very thick as it was applied with a medium brush and Hogarth let the muted colors spread naturally as they blended into the canvas.

The clothes are painted with thick paint strokes and the lines are stronger and prominent as they recreate the sweeping heavy and luxurious fabric of the sitter's dress. The figure's veil is very finely painted to reflect the nature of the material, a thin layer of paint showing the fabrics' transparency.

Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo Critical Reception

Created towards the end of Hogarth's life in 1759, Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo was, unfortunately, very badly received by critics.

Modern critics:

At a 2007 exhibition of Hogarth's work at the Tate Britain in London, the painting was described as receiving:"Some of the most damning criticism the artist ever suffered."

Brain Sewell:

"Above all things, I then accepted that Hogarth was a man who understood the nature of oil paint as a material of virtue in itself, who could contrive a balance between this nature and the nature of the materials that it was employed to depict, that he let the paint flow from the brush in such a way that throughout his work there was a spontaneity of touch,"

Sewell goes on to say: "All this may seem admirable but it was flawed by Hogarth's heavy-handedness... that his pictorial constructions, whether of single figures, small groups or a crowd, are always constrained by the same stagey limits, without rhythm, significant interval or accent"

Contemporary critics:

This painting was produced as a commission for Sir Richard Grosvenor, who let Hogarth choose the subject matter, having been impressed by the artist's other works.

Unfortunately when the painting was finished Grosvenor was not impressed with the results, describing the painting as: "So striking and inimitable, that the constantly having it before one's eyes would be too often occasioning melancholy ideas to arise in one's mind"

Insulted, Hogarth released his client from their deal and kept the painting himself. Yet, the artist decided to show it as the center piece of his exhibition at The Foundling Hospital in 1761.

The painting lasted four days and was hounded by many visitors who complained that it was void of emotion and the heart which Sigismunda is touching was too gruesome.

Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo Related Paintings

Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo Locations Through Time - Notable Sales

When Sir Richard Grosvenor rejected both the painting and its price Hogarth, insulted, released him from their agreement. He then decided to show it at an exhibition for the Society of Artists, in 1761. Bad critical appraisal meant that Hogarth removed it from displayed after only four days.

Following his death he left instructions for his widow, asking her not to sell the painting for less than £500. When Anne Hogarth died in 1789 it passed to a cousin of hers, Mary Lewis who sold it by auction in 1790 for 56 guineas.

The publisher John Boydell displayed this work in his Shakespeare Gallery, London, in 1790. The painting was sold for 400 guineas at Christie's auction house in 1807 to an unknown owner.

By 1814 it was owned by J. H. Anderdon who then bequeathed it to the Tate upon his death in 1879. Since 1879 Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo has been in the collection of the Tate Britain, London.

Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo Artist

Hogarth did, on occasion, produce historical works, such as Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo but they never received any critical acclaim and he never received any commissions for similar pieces.

The artist Joshua Reynolds is known to have dismissed Hogarth's historical works at the time they were produced: "(Hogarth) Very imprudently or rather presumptuously, attempted the great historical style, for which his previous habits had by no means prepared him"

Reynolds does go on to say that: "Hogarth's genius, been employed on low and confined subjects, the praise which we give must be limited in its object".

Hogarth himself was always very dismissive of criticism from his contemporaries and art critics of the day. In typically outspoken style he is noted to have said: "All the world is competent to judge my pictures except those who are of my profession".

Hogarth gained popularity for his morality paintings and the prints that were made from them though he also produced work in a variety of other genres including portraiture and biblical/historical pieces.

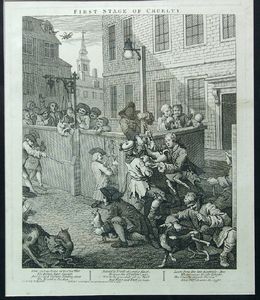

The artist was heavily influenced by 18th century life, culture and his middle-class upbringing. He believed that art should have moral as well as aesthetic qualities and tried to bring this into all the work he produced.

Having lived in debtors' lodging for five years as a very young boy, Hogarth had seen the harder side of life and brought a sense of gritty realism to all his paintings. What he believed to be the deterioration of British morals particularly concerned him and his satirical engravings illustrate his concerns for his fellow countrymen.

As Hogarth became a prominent figure in the London art scene he was influenced by a number of things. These included politics, art, literature and the theatre.

Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo Art Period

Hogarth lived and worked during the Rococo period in 18th century London. The Rococo style was popular in both England and France at this time and was embodied by flowing lines and intricate decoration.

The London social scene that features in so much of Hogarth's work ranged from super-rich aristocrats living flamboyant lifestyles to the incredibly poor working-classes with no money and little hope for a better life.

Rather than be influenced by many of the artists who had gone before him, Hogarth, a true innovator, tried to create a new school of English painting to rival the Old Masters of the Renaissance. In fact, rather than be influenced by their work it has been suggested that he often ridiculed them.

Far from being a positive influence, this style of painting pushed Hogarth to produce work of a completely different genre.

Technological advances were very influential in Hogarth's success and without the further development of the printing press his work would not have been anywhere near as lucrative, as it wouldn't have been accessible to people from the middle and lower classes.

Although Hogarth was a skilled portrait painter he became famous for his engravings which were sold in large numbers to people who would not have been able to previously afford art. His series of moral paintings, such as A Harlot's Progress and A Rake's Progress took a satirical look at the government and social scene of the day, and highlighted the best and worst parts of English culture.

As one of the first British artists to be recognized throughout Europe, Hogarth became a major source of inspiration to other artists. During his lifetime artists and satirists such as John Collier emulated his satire and reflections of everyday life. In the 19th century the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood was inspired by Hogarth's use of symbolism and text to convey a moral message.

However, it is possibly the biggest testament to the artist's skill and wit that the new medium of the comic strip arose from his work, a genre which is still popular today.

Sigismunda Mourning over the Heart of Guiscardo Bibliography

For further reading about William Hogarth please choose from the following recommended sources.

• Antal, Frederick. Hogarth and His Place in European Art. London 1962

• Bindman, David. Hogarth. London 1981

• Bindman, David, Ogée Frédéric & Wagner, Peter. Hogarth: Representing Nature's Machines. Manchester, 2001

• Fort, Bernadette & Rosenthal Angela. The Other Hogarth: Aesthetics of Difference. Princeton UP, 2003

• Shesgreen, Sean. Hogarth and the Times-of-the-Day Tradition. Cornell UP, 1983

• Simon, Robin. Hogarth, France and British Art: The rise of the arts in eighteenth-century Britain. London, 2007

• Quennell, Peter. Hogarth's Progress. New York 1955

• Uglow Jenny. Hogarth: A Life and a World. London 1997