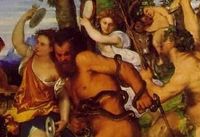

Bacchus and Ariadne

- Date of Creation:

- 1523

- Height (cm):

- 176.50

- Length (cm):

- 191.00

- Medium:

- Oil

- Support:

- Canvas

- Subject:

- Figure

- Art Movement:

- Renaissance

- Created by:

- Titian

- Current Location:

- London, United Kingdom

- Displayed at:

- National Gallery London

- Owner:

- National Gallery London

Bacchus and Ariadne Story / Theme

In Greek mythology, Ariadne was the clever, though perhaps naïve, daughter of King Minos of Crete who aided the hero Theseus in his mission to slay the Minotaur.

On the island of Crete, there was a great labyrinth (constructed by the famed Daedalus) that housed a fearsome beast - the Minotaur - that was half human, half bull. King Minos, in retaliation for his son's death at the hands of an Athenian, required the people of Athens to send seven young men and seven young women to be sacrificed to the Minotaur every nine years, or risk the complete destruction of their city.

One year, Theseus volunteered to be sent to Crete as part of the horrific sacrifice, planning to kill the Minotaur and release his countrymen from their plight. When he arrived in Crete, Ariadne spotted him and fell in love instantly.

She approached Theseus and offered to help him defeat the monster and navigate out of the labyrinth safely if he agreed to marry her. Theseus agreed and Ariadne told him how to find his way out of the maze, and gave him a sword to fight with and a ball of red thread to use to mark a path.

Theseus was successful in killing the Minotaur and winning Athens' freedom, but he had no intention of marrying Ariadne. They sailed for Athens to keep up appearances, but during a brief stop on the island of Naxos, he very un-heroically sailed away without her while she was sleeping on the beach.

Utterly distraught by her unwarranted abandonment and rejection, Ariadne was still sitting on the beach when Bacchus (known as Dionysus to the Greeks), the god of wine and revelry, appeared with a procession of his followers.

He spotted the grief-stricken Ariadne and was instantly intoxicated by her. Ariadne returned his affection and they were married, having three sons and remaining fairly happy.

Some versions of the myth say that after their wedding, Bacchus placed Ariadne's sparkling diadem in the sky as the constellation Corona, thus elevating his new wife to immortal status.

Bacchus and Ariadne Inspirations for the Work

Commission:

Titian was commissioned by Alfonso d'Este (or Alfonso I), Duke of Ferrara, to create a piece for his Camerino d'Alabastro, or alabaster room in his palace. Alfonso was commissioning all of the great Italian painters alive at the time including Raphael, Bellini and Dosso Dossi to paint glorious bacchanal scenes derived from well-known Greek and Roman mythology.

Titian also completed Bacchanal of the Andrians and The Worship of Venus for the duke's project.

In a classic case of sibling rivalry, the duke was evidently trying to emulate what his sister, Isabella d'Este, had previously done. Isabella had already commissioned a number of mythologies from all of the great Italian painters of the day to decorate one of her favorite rooms.

Mythology:

Classical Roman and Greek myths were fairly well-known in Italy during this time, especially among the educated ruling class. Titian is believed to have painted his Bacchus and Ariadne based on a rendition of the myth found in writings by Ovid in his collection called Metamorphoses.

In Ovid's version of the myth, the story of Bacchus and Ariadne is a brief vignette embedded within the larger story of Daedalus and Icarus.

Raphael:

One of the most critically acclaimed Renaissance masters, Raphael, was also commissioned to work on Alfonso's alabaster room. It was Raphael who had originally been commissioned to paint this particular scene but his unexpected death in 1520 left it incomplete.

When the commission transferred to Titian, he was given access to sketches drafted by Raphael prior to his death depicting his ideas for the work. In either a reverent nod to prematurely deceased Raphael's original ideas, or perhaps to save time (or both), Titian based his final painting on one of Raphael's original sketches.

Bacchus and Ariadne Analysis

Composition:

The main subjects of this painting are, naturally, Bacchus and Ariadne. Bacchus is positioned just to the left of center, leaping from his chariot and practically falling over himself to reach Ariadne. She occupies the far left and is half-turned away from Bacchus in fear and half-turned toward the treacherous Theseus' departing ship over her left shoulder.

The right side of the painting is quite busy, accommodating Bacchus' jovial and chaotic procession of reveling satyrs and nymphs. The way Titian has framed the painting makes the untamed forest, from whence the procession came, seem encroaching upon the open horizon and domesticated landscape that's visible behind Bacchus.

This encroachment mirrors the invasion of the wine god and his followers upon Ariadne's mournful solitude, thus perhaps hinting at the capability of the liberated to rescue those in despair.

Color palette:

Titian was the undisputed master of color during the Italian Renaissance. Taught by Bellini, another artist with an almost supernatural ease with color, Titian blended tones seamlessly, created perfect balances of warm and cool and used colors as symbols, something few others have been able to mimic.

In Bacchus and Ariadne, Titian has created a harmonious balance of color that is simultaneously symbolic. Bacchus, for instance, is loosely swathed in a billowing wine-colored robe - meant to reflect his status as the god of wine.

Ariadne wears an ultramarine robe with a scarlet scarf with the blue serving to extend the line of the sea and sky and balance the dark woodsy colors sprawling from the opposite side of the canvas. The red she wears sets her apart from the sea and sky and preserves her status as one of the primary subjects.

Some scholars have also looked into the discarded saffron colored robe near her feat as a symbol of her bitterness toward Theseus and a symbol of her shedding that chapter of her life, leaving her open to marry Bacchus, her rescuer.

Movement:

Titian has created a painting that swirls with energy and activity. He has painted Bacchus nearly falling from his chariot with his upper body lunging toward Ariadne, who seems to be negotiating how to escape without tripping over her abundant clothing.

The painting is an organized mishmash of flying limbs and fluttering robes, reflecting the frenzied nature of Bacchus' procession and indicating that it startled the distressed Ariadne, whose instinct was to flee.

Bacchus and Ariadne Critical Reception

During life:

Bacchus and Ariadne was painted for Alfonso d'Este's private collection, where it was presumably not open to the public except for those who visited the duke's home and were invited to view it in his alabaster room.

When Titian died in 1576, the paintings he had completed for d'Este were still on display in the duke's palace, where they were evidently appreciated and admired.

After death:

Great Renaissance critics, such as Vasari, made no mention of Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne, indicating that they perhaps did not know of its existence or had not seen it personally.

When the d'Este family was without a legitimate heir and lost its land holdings in 1598, however, Alfonso's vast art collection was dispersed throughout Italy where many of the masterpieces he and his descendants had unintentionally hoarded were more widely available for critique.

This led to a number of artists attempting to copy or closely imitate Titian's bacchanals, including Bacchus and Ariadne. One such imitation was produced by Luca Giordano in the mid 17th century (see above). Imitations were typically made by artists in order to practice their own skill and disseminate images more widely in an era before easy print-making and the digital age.

When the National Gallery in London acquired Bacchus and Ariadne it had already sustained some damage from being rolled up twice during its existence. So, starting in the mid-19th century, it began to receive frequent restorations to prevent the paint from flaking off.

One of the most controversial and for some, devastating, restorations occurred between 1967-68 when a discolored layer of varnish was removed, taking much of the sky with it. This damage required extensive re-painting, which has left what many critics call a flat and pallid sky, where Titian had originally painted a celestial masterpiece.

Damage and restoration aside, critics today still marvel at his Bacchus and Ariadne. Many refer to the luscious silken garments sweeping across the canvas or the sensuous color choices and rendering, naming this one of Titian's many masterpieces.

Bacchus and Ariadne Related Paintings

Bacchus and Ariadne Locations Through Time - Notable Sales

When Alfonso d'Este's grandson, Alfonso II, failed to produce a legitimate male heir by his death in 1597, the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II named his cousin, the illegitimately born Cesare d'Este as heir.

However, the Pope, Clement VIII, had aspirations to absorb the prosperous duchy of Ferrara into the Papal States and thus refused to recognize Cesare's claim.

Therefore, in 1598 the Papacy acquired the d'Este lands and estate, including its vast collection of art, due to the many generations of art lovers in the family.

Bacchus and Ariadne was evidently purchased by a man known as Hamlet, who was a wealthy jeweler, in the early 1800s. Hamlet sold it and a number of other paintings to the National Gallery, London, for £9,000 in 1826.

Bacchus and Ariadne Artist

Often hailed as a modern artist with impressionistic tendencies, Titian has been revered for centuries as a pioneering painter.

During his extended and illustrious career, he enjoyed great fame and wealth, thanks to his connections with the royalty of Europe, who constantly commissioned portraits and mythologies from him.

Titian's style is marked by an uncanny attention to color and light. He is even believed to have said that good painters really only need three colors: black, white and red.

The artist's advanced years are defined by his preference for somewhat vague forms and vibrant brushstrokes, a style seldom seen again until the 20th century.

Many of his later subjects were taken from mythology, with his chaotic brushwork only adding to the mystery and power that surround the myths. Such paintings have a way of transcending the physical - demonstrating Titian's penchant for portraying emotion such as confusion and fury.

Titian often chose to place these paintings in a nocturnal setting, perhaps acknowledging that he was now in the twilight of his own life.

Bacchus and Ariadne Art Period

Painted during the High Renaissance, Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne was both emblematic of the times and innovative in its own right. Taking cue from a number of well-established artists, especially the late Bellini and Giorgione, Titian brought the High Renaissance to Venice.

Previously, the High Renaissance in Italy had only been in full-swing in places like Rome and Florence, where artists strove to create perfectly proportioned figures with well-defined lines.

Venetian artists during this time preferred color and blending to exacting proportions, which caused something of a rift between the two Renaissance camps.

Bacchus and Ariadne Bibliography

For further reading on Titian, please choose from the following recommended sources.

• Biadene, Susanna. Titian: Prince Of Painters. Marsilio Editori, 1990

• Bowron, Edgar Peters. Titian and the Golden Age of Venetian Painting (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston). Yale University Press, 2010

• Hudson, Mark. Titian: The Last Days. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2009

• Humfrey, Peter. Titian. Phaidon Press Ltd, 2007

• Ilchman, Frederick, et al. Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese: Rivals in Renaissance Venice. Lund Humphries, 2009

• Pagden, Sylvia Ferino & Scire, Giovanna Nepi. Later Titian and the Sensuality of Painting. Marsilio,Italy, 2008