Vision after the Sermon

- Date of Creation:

- 1888

- Alternative Names:

- Jacob Wrestling with the Angel

- Height (cm):

- 72.20

- Length (cm):

- 91.00

- Medium:

- Oil

- Support:

- Canvas

- Subject:

- Fantasy

- Framed:

- No

- Art Movement:

- Post-Impressionism

- Created by:

- Current Location:

- Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- Displayed at:

- National Galleries of Scotland

- Vision after the Sermon Page's Content

- Story / Theme

- Inspirations for the Work

- Analysis

- Critical Reception

- Related Paintings

- Locations Through Time - Notable Sales

- Artist

- Art Period

- Bibliography

Vision after the Sermon Story / Theme

Genesis 32: 22-31

"The same night he arose and took his two wives, his two maids, and his eleven children, and crossed the ford of the Jabbok. He took them and sent them across the stream, and likewise everything that he had. And Jacob was left alone; and a man wrestled with him until the breaking of the day."-

Vision after the Sermon

Gauguin:

"I have just painted a religious picture, very clumsily; but it interested me and I like it. I wanted to give it to the church of Pont-Aven. Naturally they don't want it."

-

Vision after the Sermon

Vision after the Sermon, also commonly known as 'Jacob Wrestling with the Angel' is one of Paul Gauguin's best known works, painted after his break with Impressionism.

The literary source for the artwork is Genesis 32: 22-31. Gauguin's painting shows the river Jabbok in the upper right-hand corner and a tree, field and wrestling figures. Traditionally, the story entails Jacob struggling with his conscience, with other men, and God represented by the angel in a struggle for truth and redemption. After the struggle and blessing, Jacob was able to continue his journey, crossing the river into the Promised Land - seen in the distant background of the image. In this biblical context, the red field is significant, differentiating between the lands of struggle from the land of peace.

The apple tree of knowledge in the painting symbolizes man's decision to comprehend good and evil, caused by his fall from grace. Its green foliation also symbolizes the promise of man's redemption and return to Paradise. In the foreground of the painting, 12 Breton women and a priest watch the event. 12 is a significant number in itself, representing Jacob's progeny in founding the 12 tribes of Israel.

Gauguin also includes a cow in the painting, further adding to the symbolism. The cow is the symbol that reveals the means of man's redemptions. In addition to its traditional meaning, the cow is the symbolic of four Breton saints venerated as protectors of horned beasts (Saints Cornley, Nicodeme, Herbot, and Theogonnie). This links with Gauguin's actual experience in Breton, where according to custom, each of the saints is given a commemorative celebration in either August or September. Through the blessings of these saints, animals and pastures are made fertile and the sick are healed.

The Chapel of Saint Nicodemus in Brittany, and its surroundings have also been depicted.

Vision after the Sermon depicts Gauguin's subjective reactions to his experience synthesized and transformed into an expression of man's struggle to understand life, his need for reconciliation with his own conscience, fellow man, nature and God. This is presented in his analogy to the ancient Celtic and Breton customs.

Gauguin tried to present Vision after the Sermon as a gift to a local church (two churches in fact) but was rejected on the notion that he was not serious or that it would scare the parishioners.

Vision after the Sermon Inspirations for the Work

In modern theology the notion of Jacob's struggle with the angel is concerned with the inner struggle that takes place in every Christian's soul. For 19th-century Romantics, Jacob came to represent the artist, wrestling with nature to reveal its secrets. Eugène Delacroix's mural of Jacob Wrestling with the Angel (1861) in the Church of Saint-Sulpice, Paris, established a lot of interest in the subject among artists in France in the mid-19th century. Gustave Doré (1866) and Gustave Moreau (1878) also made works on the subject of Jacob, which Gauguin would most probably have seen.

Paul Gauguin's Vision after the Sermon exemplifies his interest in a new aesthetic and break from Impressionism. This break can be seen as the result of experiences traveling to Brittany (1885-86) and Martinique (1887), where he sought new creative energy away from corrupted urban centers and to live with nature as a 'savage'.

Through these experiences and his friendship with van Gogh, Gauguin developed the confident style and distinctly eloquent lines we see in Vision after the Sermon. On his second visit to Pont-Aven he wrote to his artist friend, and one time fellow stockbroker, Claude-Emile Schuffenecker -

"Give me the country. I love Brittany; I find in it the savage and the primitive."

During the same year in Brittany, Gauguin introduced the color red into his landscapes, suggesting the influence of Japanese prints (of which he owned), with flat blocks of color and linear divisions of the picture plane. Dramatic red is used with great affect in Vision after the Sermon. Gauguin's use of non-naturalistic elements, dramatic seriousness in the severity of mood, allowed him to convey the religiosity of the local people in this work.

Vision after the Sermon Analysis

Composition:

Gauguin's Vision after the Sermon heralds his arrival as a Synthetist artist. This artwork includes peasant women leaving the church in the lower part of the canvas, and above them is a vision of Jacob wrestling with the Angel - probably the sermon of the day. Gauguin combines two levels of reality in the one composition, both the real and the dream world. The design is so strong that the two realities are fused into one visual experience.

The daring color and dramatic composition of Vision after the Sermon are in great contrast to most work in the 1880s, where a photographic representation of nature was deemed necessary for art. Gauguin is able to instill in the image a spiritual resonance through his arbitrary use of primary color and the distortion of visual truth. The intuitive images that later formed the basis of the Surrealist movement in art, and the formal manipulation of the picture plane that preoccupied Abstract Expressionists, were used in Vision after the Sermon in a wholly original and daring manner.

Color palette:

The distinction between the observation and the actual vision, plus the fusion of the two onto the one pictorial plane is made most powerfully through color. The women in the foreground are painted in harshly contrasting black clothes and yellow-white bonnets. Gauguin himself described the ground on which Jacob and the Angel wrestle as "pure vermillion" and the figures as "violent ultramarine, bottle green, pure chrome-yellow, and orange."

Vision after the Sermon's background is painted in a flat red to emphasize the mood and subject of the sermon - Jacob's spiritual battle fought in a blood red field of combat. Gauguin believed that colors had a mystical quality that could express feelings about a subject in addition to simply describing a scene.

This artwork ignores the rules of perspective. The figures on the foreground are too large and almost block the view of the wrestlers, who would normally have been central to the composition.

Use of light:

In Vision after the Sermon Gauguin uses stylized images for the Breton figures in a shallow pictorial space with a "vision" in the top right corner. The real and imagined worlds are separated by the strong, diagonal of a tree, which was inspired by Japanese prints. Gauguin had studied these and adopted their use of bold, flat areas of solid color. The lower figures of the painting are reduced to areas of flat patterns, without modeling, whilst the large color areas are intense and without shadows.

Brush stroke:

Drawing the images before setting paint down on the canvas underpinned Gauguin's painting and served a number of purposes. His sketchbooks of this period are often interspersed with diagrams, notes, names and addresses in preparation for Vision after the Sermon. Gauguin did many drawings of the intricate Breton ceremonial headdresses noting the variations worn for work, formal occasions and for mourning. His illustrations on ceramics possess a simple, somewhat primitive drawn quality and heavily influence his painting style.

Vision after the Sermon Critical Reception

Vision after the Sermon is an exciting and dramatic work using clear-cut shapes of black and white against a dramatic red background. Given its complexity, few paintings of the period have instigated more analysis, critique, speculation, than Vision after the Sermon. In terms of contemporary and artistic historical significance, this artwork has been referred to recently as the greatest of Gauguin's works, and the key by which all the doors of the 20th-century art were unlocked.

Furthermore, in Gauguin's own lifetime Vision after the Sermon was described as prodigious, illuminating and capable of giving the initiated access to hidden mysteries.

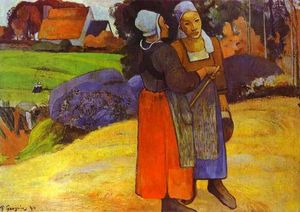

Vision after the Sermon exerted a significant influence on other artists, and from the time after he finished this work Gauguin's status among fellow artists changed. He was considered the leader of a new Symbolist artistic movement by some, but resented by others. Indeed, Emile Bernard believed that his own Breton Women in the Meadow (1888) was the source for Gauguin's painting and accused him of plagiarism.

Art expert Belinda Thomson:

"In this remarkable picture Gauguin succeeded in imbuing a deliberately crude and simplified composition with a higher level of sophistication, raising it to a higher plane of meaning. His masterpiece resulted from a slow distillation and sudden insight: an awareness of widely different traditions of art; a readiness to work with those traditions but cast them in a new, reinvigorated style; an ability to imagine afresh an ancient story through reference to contemporary customs and religious practices. "

Vision after the Sermon Related Paintings

Vision after the Sermon Locations Through Time - Notable Sales

Vision after the Sermon was purchased by the National Gallery (where it has since stayed) in 1925 for £1,150 by the then director, James Caw. At the time the purchase must have seemed a courageous choice given the widespread antipathy the British public had for Post-Impressionism as exhibited at Roger Fry's exhibitions in London in 1910 and 1912. However, the purchase proved fortuitous, and the National Gallery's status has been upheld internationally due to Vision after the Sermon.

Vision after the Sermon Artist

Paul Gauguin was one of the most talented artists of the 19th century. His work has been categorized variously as a Post-Impressionist, Synthetist and Symbolist. Gauguin is well-known today for his turbulent creative relationship with fellow artist Vincent van Gogh, and his eventual self-imposed exile to Tahiti.

Deeply affected by exotic identity (Gauguin's mother was of Peruvian descent), he paved the way to Primitivism, and was an expert exponent of wood engraving and woodcuts.

Gauguin's Vision after the Sermon was painted in one of his many interpretations of the Brittany scenes in 1888. After years of lecturing his fellow artists on the importance of returning to nature and painting as if in a dream and not reality, this was his first breakthrough in truly achieving his ideal in art. It also cemented his renown among his artistic contemporaries. Gauguin's breakthrough was perhaps the result of years grinding away in poverty.

Vision after the Sermon Art Period

The Vision after the Sermon heralded Gauguin's break with naturalism and the transformation to a new Synthetist style, which involved working from memory and imagination to eliminate the essentials. The artwork is influenced by Symbolism, which encouraged a spiritual approach.

With Vision after the Sermon Gauguin began his symbolist project of solemnity in religious meditation, by making a clear distinction between what is real (people praying) and what is imagined (the religious vision). After intensifying his tones, giving them greater purpose and power, Gauguin moves his colors well beyond those of reality, representing his own movement into the world of imagination, vision and dream and into the world of Symbolism, a world including, but not subservient to Christian iconography.

Vision after the Sermon Bibliography

To learn more about the life and works of Paul Gauguin please refer to the following recommended works.

• Eisenman, Stephen F. Paul Gauguin: Artist of Myth and Dream. Skira Editore, 2008

• Gayford, Martin. The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Arles. Penguin, 2007

• Gauguin, Paul. Noa Noa: The Tahiti Journal of Paul Gauguin. Dover Publications Inc. , 1985

• Schiff, Richard, et al. Gauguin: The Origins of Symbolism. Philip Wilson Publishers Ltd, 2004

• Shackelford, George T. M. & Freches-Thory, Claire. Gauguin Tahiti: The Studio of the South Seas. Thames Hudson, 2004

• Thomson, Belinda. Gauguin: Maker of Myth. Tate Publishing, 2010