The Hay Wagon

- Date of Creation:

- 1515

- Alternative Names:

- The Haywain

- Height (cm):

- 147.00

- Length (cm):

- 212.00

- Medium:

- Oil

- Support:

- Wood

- Subject:

- Fantasy

- Web Page:

- http://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/online-gallery/on-line-gallery/obra/the-hay-wagon/

- Art Movement:

- Renaissance

- Created by:

- Current Location:

- Madrid, Spain

- Displayed at:

- Museo Nacional del Prado

- Owner:

- Museo Nacional del Prado

- The Hay Wagon Page's Content

- Story / Theme

- Inspirations for the Work

- Analysis

- Critical Reception

- Related Paintings

- Artist

- Art Period

- Bibliography

The Hay Wagon Story / Theme

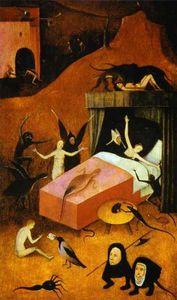

The Hay Wagon is derived from the Flemish proverb "The world is a haystack, and each man plucks from it what he can. " A haystack in this sense is a biblical metaphor of earthly fame, wealth and ephemeral desires that can be both corruptive and worthless. The demons in the image take advantage of men's pursuit of such desires and attempt to pull them into hell.

This work also illustrates a verse from Isaiah (Isaiah 40: 6-7) "All flesh is grass, and all the goodliness thereof is as the flower of the field: The grass withereth, the flower fadeth. "

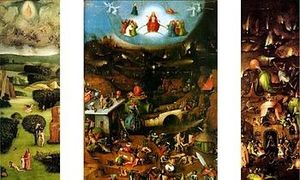

Once opened, this triptych deals with sin and its consequences. On the left panel the viewer sees the origin of sin on earth, from the fallen angels to Eve's sin and the center panel depicts humanity being dragged into sin. Men and women surround the hay wagon and everyone wants to climb onto it, fighting for a share of the hay.

Even kings, bishops and aristocrats pursue the hay wagon. These people feel no shame in engaging in crimes to access the hay and will go as far as killing others to do so.

In the bottom right corner a group of priests and nuns have already obtained a sack of hay and they can be seen dividing, storing and savoring it. Caught up in the fight nobody is aware that demons are pulling the wagon into hell in the right panel.

The closed triptych shows an old pilgrim walking the path of life, overwhelmed by danger.

Another version of The Hay Wagon can be found in the monastery at El Escorial and this is thought to be the one Felipe II bought from Felipe de Guevara in 1570. The work discussed here and on display in the Museo Nacional del Prado must have also belonged to Felipe II, even earlier than Guevara's, but the first record of this is the 1636 inventory of the Alcázar Palace in Madrid.

The Hay Wagon Inspirations for the Work

A lack of information about Bosch, his life and inspirations, hinders an understanding of his imagery in The Hay Wagon and any interpretation of it. What is known, however, is that Bosch belonged to the Brotherhood of Our Lady, a religious group that focused its attentions on the Last Judgment, eternal damnation and the universal demons of evil.

Bosch did not paint demons and hellish landscapes to celebrate their existence; rather his artworks try to inform people that good will be rewarded with good and evil with evil. His art was a way of showing people how to behave and act in a manner that was morally right and in accordance with God's laws.

Moreover, Bosch worked at a time when the medieval period was coming to an end and therefore his paintings most probably reflect his anxiety over a changing world. Many of the paintings Bosch produced are similar to the works created by the Surrealists centuries later. They too paint a world based on fantasy and therefore Bosch's works are strangely modern. His popularity among contemporary artists and art fans has thus been strong.

Aside from the fantastical and grotesque elements of Bosch's works which made him a precursor to the vision of the Surrealists, the lasting beauty of paintings such as The Hay Wagon stems largely from Bosch's vivid color and brilliant technique, which was much more fluid than that of most of his contemporaries.

The Hay Wagon Analysis

Narrative:

The Hay Wagon is similar to The Garden of Earthly Delights with its progression of sin across its panels, from the Garden of Eden to hell. Early Renaissance works usually employed this technique, to present scenes in chronological order so that they can be read like a story. Yet, in The Hay Wagon, a narrative sequence flows through the panel in different events.

Composition:

At the top, rebel angels are banished from Heaven while God sits on his throne with a globe in his hand, representing the universe. As the angels break through the clouds they turn into insects.

Below God creates Eve from Adam's rib. The couple then discovers the tree and the serpent who offers them an apple. In the lower part of the panel, Adam and Eve are forced out of the Garden of Eden by an angel. Adam talks to the angel while Eve looks ahead to the right in a despondent pose.

The Garden of Earthly Delights focuses on the sin of lust but in The Hay Wagon people engage in a range of sinful behavior. The greedy world tries to grasp the wagon which is unknowingly being dragged into the depths of hell and the viewer cannot help but be dragged along with them on their journey from present-day sin into horrific torture. This was one of Bosch's earliest illustrations of hell.

Use of technique:

The style used for this triptych is similar to that of watercolor.

Mood, tone and emotion:

On the left side of this panel the convoy bends back into the middle ground, but on the right the figures move in a straight line, representing a progression into damnation.

The Hay Wagon Critical Reception

As there is little evidence of Bosch's influences and patrons, it has been extremely difficult for art historians to interpret Bosch's works and understand his distinct mode of expression. Yet, scholars have debated his iconography more widely than any other Netherlandish artist.

In the twentieth century, when changing artistic tastes meant that Bosch captured the European imagination, some argued that his art was inspired by heretical points of view. Due to the fact that the writer Erasmus was educated at one of the houses of the Brethren of the Common Life in 's-Hertogenbosch, a town that was religiously progressive, some find it unsurprising that there are links between the scathing writing of Erasmus and the works of Bosch.

Others claimed that Bosch's work was produced to titillate and amuse, much like the "grotteschi" of the Italian Renaissance. Unlike the art of the older masters which was based in the physical world of everyday life, Bosch's paintings were confrontational and according to art historian Walter Gibson they offer, "a world of dreams [and] nightmares in which forms seem to flicker and change before our eyes. "

More recently, scholars have regarded Bosch's vision as less fantastic, and accepted that his art mirrors the orthodox religious belief systems of his age. His portrayals of sinful humanity and representations of good and evil, as seen in The Hay Wagon, are now seen as in-keeping with those of late medieval didactic literature and sermons. Thus, most writers attach a greater significance to his paintings than before and try to attempt to interpret it in terms of a late medieval morality.

Generally, it is thought that Bosch's art was created to teach specific moral and spiritual truths in the same way as other Northern Renaissance figures, such as the poet Robert Henryson, and that his imagery has exact and premeditated meaning. Yet, conflicting interpretations of Bosch's works still exist and these raise important questions about the nature of "ambiguity" art of his era.

The Hay Wagon Related Paintings

The Hay Wagon Artist

Hieronymus Bosch dedicated his entire career to producing works that broke away from traditional Flemish painting. His work used vivid imagery to depict moral and religious ideas and stories, and he set himself apart from his contemporaries with the disturbing detail of his panel pictures, perfectly exemplified in The Hay Wagon.

Produced in the middle stages of his career, triptychs like this were highly ambitious projects to undertake and Bosch successfully merges elements of fantasy and chaos with pleasant scenes of mankind in the age of innocence. Such works were evidence of his developing thought processes and the evolution of his unique style.

Relying heavily on symbolism and working freely, many of Bosch's paintings addressed the torments of hell and his later pieces in particular were highly original and sometimes offered a literal translation of verbal metaphors set out in the Bible. Both wonderful and terrifying, his works were unforgettably garish and his technique remains unmatched to this day.

The Hay Wagon Art Period

The Early Netherlandish Renaissance essentially began with the work of Jan van Eyck and came to an end in around 1520. This artistic period evolved with the early and high Italian Renaissance but is seen as a distinct artistic culture that was independent of the humanist developments taking place in central Italy.

As Early Netherlandish painters such as Bosch represent the medieval artistic heritage in northern Europe and respond to Renaissance principles, their works can be classified as both Early Renaissance and Late Gothic.

Paintings from this period adopted Jan van Eyck's attention to detail and usually featured byzantine iconography. Religion was a popular theme, as were small portraits. Narrative and mythological works were much less common than in Italy.

Hieronymus Bosch worked at a time when the medieval period was coming to an end and therefore his paintings most probably reflect his anxiety over a changing world. Many of the paintings he produced are similar to the works created by the Surrealists centuries later.

The Hay Wagon Bibliography

To find out more about the life and works of Hieronymus Bosch please choose from the following recommended sources.

• Bosch, Hieronymus. Bosch - The Complete Paintings. Granada Publishing, 1980

• Bosing, Walter. Hieronymus Bosch 1450-1516: Between Heaven and Hell. The Complete Paintings. Taschen GmbH, 2001

• Copplestone, Trewin. The Life and Works of Hieronymus Bosch. Shooting star press, 1995

• Gibson, Walter S. Hieronymus Bosch. Thames & Hudson, 1973

• Harris, Lynda. The Secret Heresy of Hieronymus Bosch. Floris Books, 1995

• Silver, Larry. Hieronymus Bosch. Abbeville Press Inc. , 2006