Cantoria

- Alternative Names:

- Singing Gallery

- Date of Creation:

- 1439

- Height (cm):

- 348.00

- Width (cm):

- 570.00

- Medium:

- Other

- Subject:

- Scenery

- Created By:

- Current Location:

- Florence, Italy

Cantoria Story / Theme

In the first quarter of the fifteenth century, the Operai del Duomo of Florence initiated a program to decorate the inside of the Duomo and the two sacristy doors. The plan to provide decoration for the Duomo's organ (perghamo degli orghani) was first conceived in 1430, when the commission for the work was given to Luca della Robbia. At the time, Donatello was still in Rome. He returned in 1433 and was given the commission of a second "perghamo" with the stipulation that the cost of his work was not to exceed that of della Robbia's.

For that reason, the two works ended up being almost exactly the same size and looking very much the same. Both men decorated the surface of their respective galleries with putti (nude, chubby, dancing children); however, their styles were markedly differently. Where della Robbia concentrated on bringing out the realness of the children, Donatello drew inspiration from antiquity and classic styles. Donatello's children are all winged and wear simple shift garments.

Cantoria Inspirations

As with nearly all of his works, Donatello drew inspiration for the Cantoria from the classic art of Greece and Rome. Throughout his career, Donatello consistently sculpted in such a way as to merge the ideals of both periods - the Renaissance's emphasis on realism and humanism, and Classicism's love of beauty, order and style. The naked, pudgy, dancing children (putti) he sculpted on the gallery's surface are clear evidence of this.

Donatello sculpted the Cantoria for the Operai del Duomo di Firenze, the choir that regularly sang in the Duomo. The Cantoria was intended to provide standing room for members of the choir, hence its nickname "Singing Gallery".

Cantoria Analysis

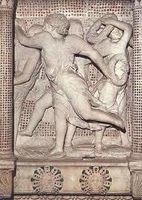

Donatello's Cantoria features two levels. On the upper level, there is an uninterrupted frieze of putti dancing about in various directions. There is no flow of movement in any one direction, and some of the putti are hidden by columns carved into the marble, suggesting that they are running around behind the columns.

On the lower level, Donatello composed four separate squares divided by heavily sculpted consoles. There are two bronze roundels and two plaques with pairs of putti surrounding a central object.

The work's entire surface is covered with a variety of antique and medieval decorations including rosettes, egg and dart, seashells, vases and acanthus. For hundreds of years scholars have claimed that knowing that the gallery would be installed far above eye level, Donatello deliberately left his sculptures in a rough-and-ready state, presumably so that the eye would be better able to adjust to them.

Yet, recent evidence proves that this is not so. Donatello was not one to leave things rough or unfinished; evidence proves that he had an extremely tight deadline, along with other projects he was working on simultaneously. The roughness of his sculptures was not an aesthetic decision, but a necessity given time constraints.

The actual subject of Donatello's Cantoria has never been clear. Scholars throughout the centuries following the Cantoria's creation have ventured many guesses, none of which has proven satisfactory.

Cantoria Critical Reception

Donatello's Cantoria is not among his most valued works but it is one of the most famous for its unique subject matter and unusual purpose. The Cantoria was designed to hold choir members in the Duomo as they sang together. It was not a large gallery and was eventually removed because it was deemed too small to hold as many members as needed.

The Cantoria is also often criticized because it does not reflect Donatello's best efforts. Because he was working to a tight deadline and had many other projects to complete, Donatello's work on the Cantoria was somewhat lacking, comparatively speaking.

For example, the figures were not finished completely; some scholars have argued that this was intentional: given the height at which the gallery would be viewed, the rough-and-ready nature of the carvings would make it easier for the eye to adjust to them.

However, this is completely out of character with the way Donatello typically worked and in all likelihood is untrue. The Cantoria, therefore, despite being a beautiful and unique work, was not very well received at the time.

The Cantoria was removed from its original position in 1688 for a Medici wedding and was never returned, providing further evidence of the city's ho-hum reception of the gallery.

Cantoria Related Sculptures

Cantoria Locations Through Time - Notable Sales

Donatello's Cantoria remained in the Duomo from 1439 until 1688, when the wedding of a member of the Medici family necessitated its removal. It was never returned to its original place, however, and records of its whereabouts are unavailable from that point on.

Scholars speculate that some of its parts may have at least briefly been used for other purposes (though these purposes are not specified). The Cantoria was probably reconstructed around the time of the Second World War and is today very probably incomplete.

The Cantoria can today be found in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo in Florence.

Cantoria Artist

Donatello was one of the most talented and influential artists of the entire Renaissance. He was born in Florence, the son of a wool-carder, and spent his youth training for what would become a truly glorious career. He was first apprenticed to a goldsmith, then to the Italian master Lorenzo Ghiberti but struck out on his own aged 17.

Donatello followed contemporary Filippo Brunelleschi to Rome, where the two young men spent years excavating the ancient grounds and fine-tuning their respective crafts - sculpting for Donatello, architecture for Brunelleschi.

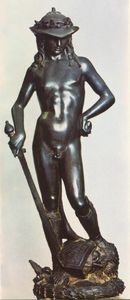

When Donatello returned to Florence, he did so an established and very highly-respected artist, having produced such works as the bronze David and received commissions from several prestigious patrons.

He was a favorite and lifelong friend of Cosimo de Medici, who petted and feted him throughout their friendship and kept him busy with commissions almost until his death.

Donatello was famous for his striking ability to merge the stylized ideals of classicism with the realistic, humanized techniques of the Renaissance in a way that seemed completely seamless and natural. He is today revered for urging the art world into the High Renaissance and left us with many priceless works.

Cantoria Art Period

The Early Renaissance was a time of immense growth and change. At Donatello's birth, the art world was still crawling out of the International Gothic period. Donatello, however, had studied classic art and was determined to pull the art world out of stagnation and into the future.

Except for Donatello, the Early Renaissance is characterized mostly by its highly stylized nature and emphasis on physical perfection. The human form, imperfect as it is, was not celebrated in Gothic art; instead, artists eliminated the imperfections as they worked to create a seamless, unnatural appearance.

Most art was religious in theme and very staid; no artist had dared to explore "deviant" interpretations of revered saints and icons. Donatello, however, challenged traditional images of, for example, David and Mary Magdalen. Whereas David had always been presented as heroic, youthful, and modest, Donatello presented him as nude, highly sexualized, effeminate, and faintly defiant.

The traditional long blond hair, beautiful features and voluptuous body of Mary Magdalen were replaced by Donatello with stringy, unwashed hair and an otherwise skeletal frame. In short, the Early Renaissance was about shy experimentation in part, but also largely about maintaining the status quo.

Cantoria Bibliography

To read more about Donatello and his works please choose from the following recommended sources.

• Bennett, Bonnie A. & Wilkins, David G. Donatello. Moyer Bell Limited, 1985

• Janson, H. W. Sculpture of Donatello. Princeton University Press, 1979

• Lightbown, R. W. Donatello and Michelozzo: Artistic Partnership and Its Patrons in the Early Renaissance. Harvey Miller Publishers, 1980

• Lubbock, Jules. Storytelling in Christian Art from Giotto to Donatello. Yale University Press, 2006

• Poeschke, Joachim. Donatello and His World: Sculpture of the Italian Renaissance. Harry N Abrams, 1993

• Pope-Hennessy, John Wyndham. Donatello: Sculptor. Abbeville Press, 1993

• Rea, Hope. Donatello. Forgotten Books, 2010

• Scott, Leader. Ghiberti and Donatello: With Other Early Italian Sculptors. Bibliolife, 2008